Real quick now: What are the first things that come to your mind when you think of the Texas frontier? Cowboys? Check. Rangers? Check. Indians? Check. Mexicans? Check. But how about paleontologists? Did you think about them, too? Fossil hunters...

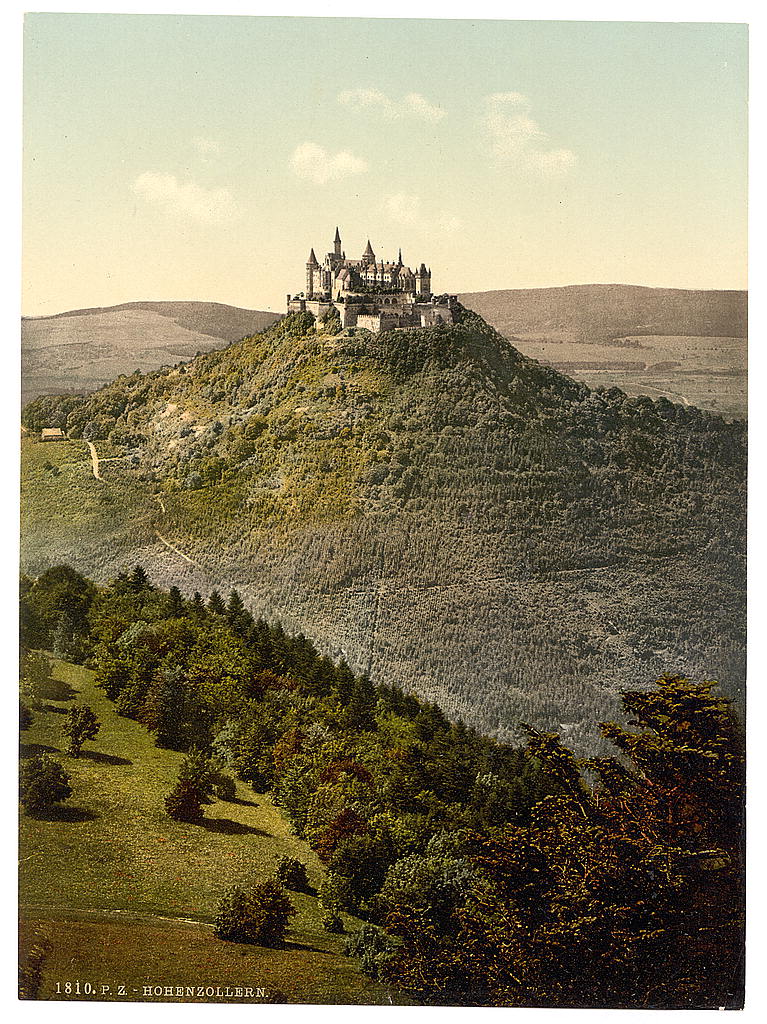

Germany as a haven after the Lincoln assassination One of the lesser known aspects of the Lincoln assassination is the aftermath that played out in Germany. All the surviving occupants of the presidential box at Ford’s theater ended up moving to...

The lives of our forefathers send ripples through the generations, shaping who we are today. If one of those forefathers happened to be a U.S. President, he shaped both national and familial history. And if that forefather was assassinated in...

A royal funeral makes criminal history Black plumes bounced on the horses’ heads as they pulled the hearse through the rain and mud. The muffled hoofbeats foreshadowed change. Neither horse nor guard nor mourner could know the path before them led...

Recent Comments