No other arrow in history has set so many quills into motion as William Tell’s apple shot. Tell’s composure and courage have thrilled composers and poets alike. Rossini’s overture and Schiller’s dramatization are only two expressions of admiration...

I recently helped solve a crime. All because I knew when to call the police. On the bus, several passengers — about 10 of us — overheard another passenger talking on her cell phone. She mentioned a theft one of her companions had just...

People love them. Restaurants hate them. And that’s why the law had to step in. When a European vintner suspends a bush, broom, or ivy bunch outside his door, that signals the sale of homemade wine and cheap, country food on his farm. The “vintner’s...

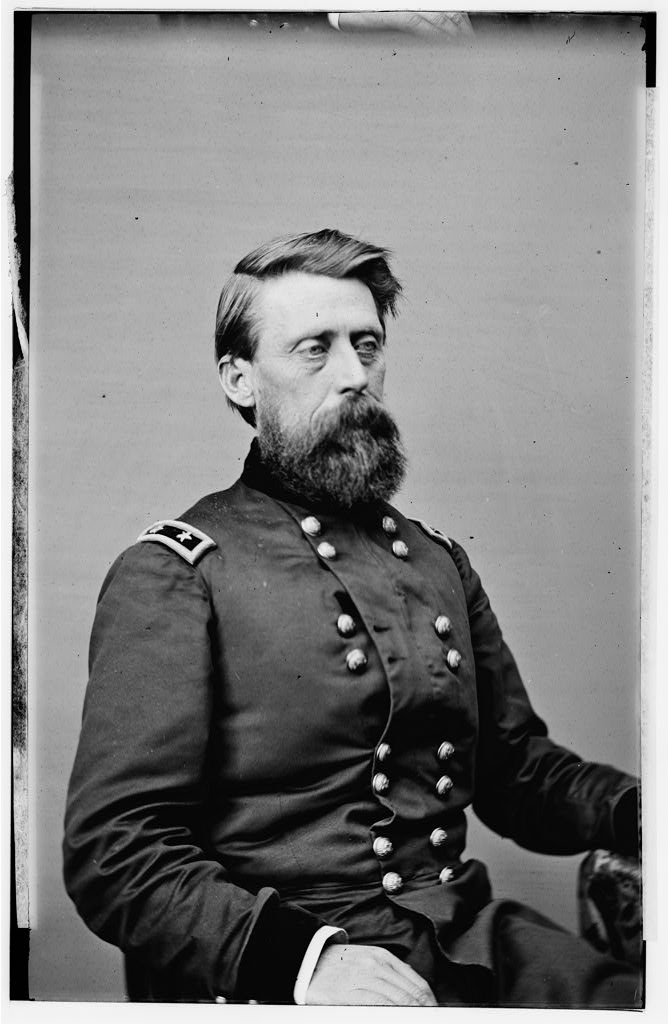

Part Two: The Offender, Jefferson C. Davis It was a shot that echoed through Civil War history, but not through the corridor separating North and South. When one Union General, Jefferson C. Davis, aimed a pistol at another Union General, William...

Recent Comments