It was a perfect murder. Well, almost. The victim’s body lay undetected for over 5,000 years, and even after it was discovered, it took a decade for scientists to realize they were dealing with a murder victim. Forensic analysis of the Iceman...

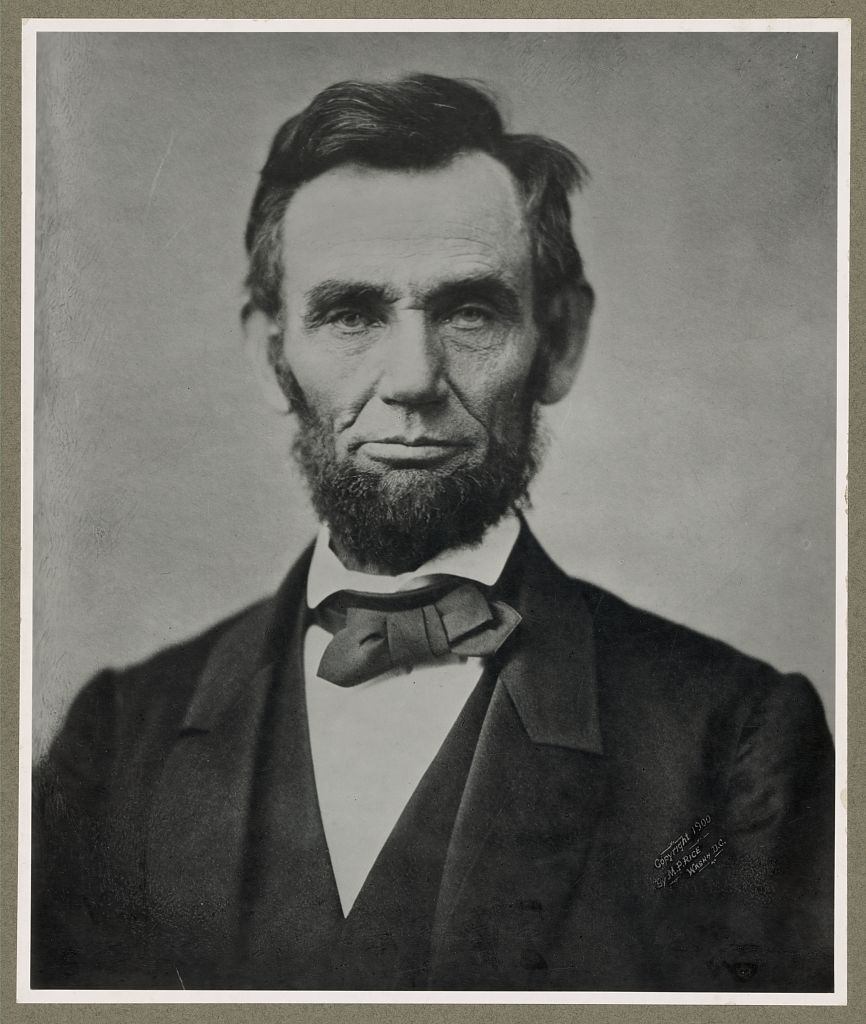

Who knew? Abraham Lincoln picked up his pen not only to scratch out the Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural Address. He also wrote poetry and true crime. His one true crime short story, published in the Quincy Whig in April 1846, is based on a...

His parents assumed he was dead. The grave digger did too. Well, maybe. If he thought it was strange that the corpse of the six-year-old child, two days after his purported death, vomited and hadn’t yet entered rigor mortis, he didn’t do anything...

Where can you find the greatest number of true crime titles under one roof? Laura James, attorney and true crime author, recently posted a blog about the Borowitz collection at Kent State University. Albert Borowitz himself published about...

Sherlock Holmes had his magnifying glass. A modern detective will bring things like evidence tags, fingerprint kits, and latent bloodstain reagents. What did a 19th-century detective pack into his forensic kit to bring to a crime scene? Let’s ask...

Recent Comments