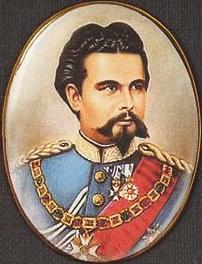

Hot evidence in a cold case New evidence in a 130-year-old unexplained death? It’s unusual, but it can happen. In the case of the mysterious death of Bavaria’s King Ludwig II, the new evidence takes the form of Dr. Gudden’s death mask. Munich’s...

You don’t need a pistol to rob a bank. A pen will do nicely, too. As the American Civil War drew to a close, a 19th-century forgery conspiracy proved that point quite nicely. Dressed as elegant businessmen, the crooks robbed banks with pen and paper...

Watergate burglary of the 19th century It was 2:00 a.m. on December 14, 1874 when the burglar alarm went off. None of the residents in Holmes van Brunt’s house on Long Island could have known that the clanging alarm would earn its place in the...

Recent Comments