Watergate burglary of the 19th century

It was 2:00 a.m. on December 14, 1874 when the burglar alarm went off. None of the residents in Holmes van Brunt’s house on Long Island could have known that the clanging alarm would earn its place in the history of burglar alarms. For its connection to a nationally publicized crime and its role in unraveling it, the break-in that night was the Watergate burglary of the 19th century.

Holmes van Brunt heard the alarm in his bedroom and sent his son Albert out to the house next door, where the alarm had been set. He thought maybe the wind had blown open a shutter and triggered the alarm. Albert grabbed a lantern and pistol and walked over. But he stopped dead in his tracks when he saw a light on in the house and shadows passing behind the window. That house belonged to his uncle, the judge, and no one was supposed to be there right now.

If anyone understood the importance of protecting his home, Judge Van Brunt did. His caseload in New York City had included plenty of thefts and burglaries. Now he sat in the New York Supreme Court and heard appeals on such cases. He knew the importance of protecting his vacation house on Long Island against burglary.

So he installed a burglar alarm designed to ring at his brother Holmes’s house next door.

History of burglar alarms

If it surprises you that people used electromagnetic home security systems as early as 1874, you should crack a volume on the history of burglar alarms.

Animals offered the most popular home security before 1700. Watchdogs, geese, and even pigs sounded an alarm if strangers approached a house. In the early 18th century, that started to change. Homes and businesses saw a move to mechanical systems. Tildesley, an English inventor, mechanically linked door locks to sets of chimes. A skeleton key in the lock set the chimes a-ringing and offered a new kind of home security.

The idea spread to the American colonies. In the early 1700s, a bank in Plymouth, Massachusetts earned a place in the history of burglar alarms by installing what was perhaps the world’s first mechanical bank alarm. It used a tripwire that ran from the safe’s door handle to the cashier’s house next door.

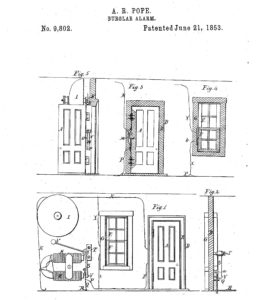

By 1852, someone figured out how to harness electricity to fend off burglars. Albert Augustus Pope, a Massachusetts minister, fitted magnetic contacts and metal foil to windows and doors. If someone tried to move them, the system sounded a bell. Edwin Holmes bought Pope’s patent in 1857 and began marketing the electromagnetic burglar alarm in New York City. At first, customers were skeptical about the device, but by 1866, Holmes had already outfitted 1200 homes with an alarm.

Then along came a burglary that showcased the alarm and gave it national publicity.

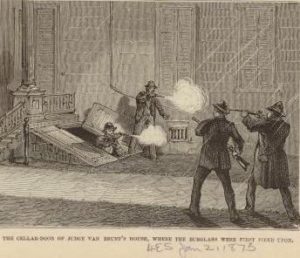

The Van Brunts confront two burglars

Albert raced back home to tell his father there really was a break-in in the judge’s vacation home next door. Holmes and Albert Van Brunt, together with a neighboring gardener and a second hired man, armed themselves with guns and took positions at the front and back doors. Holmes and the hired man entered the judge’s house from the rear. Holmes then opened the trapdoor to the pantry and discovered two men there. Testimony at the coroner’s inquest indicates the burglars fired first. Team Van Brunt returned the fire and shot two men. One, William Mosher, died at the top of the pantry stairs; the other, Joseph Douglas, made it out to the front lawn before he collapsed. Douglas died three hours later, but not before he made a confession. “It’s no use lying now. I helped steal Charlie Ross…. Mosher knows all about it.”

Testimony at the coroner’s inquest indicates the burglars fired first. Team Van Brunt returned the fire and shot two men. One, William Mosher, died at the top of the pantry stairs; the other, Joseph Douglas, made it out to the front lawn before he collapsed. Douglas died three hours later, but not before he made a confession. “It’s no use lying now. I helped steal Charlie Ross…. Mosher knows all about it.”

“It’s no use lying now. I helped steal Charlie Ross…. Mosher knows all about it.”

Douglas had just confessed to one of the worst crimes of the century: the kidnapping of four-year-old Charlie Ross. In fact, the judge who presided over the trial of one of the burglars’ co-conspirators said it was widely regarded “as the worst crime of the century.” Those words were particularly astonishing in August 1875, when the horror of the Lincoln assassination still held the American public in its grip. Why was the kidnapping of a boy worse than the assassination of the president?

Charlie Ross: snatched from the street

Charlie Ross and his five-year-old brother Walter had been playing in front of their home in Philadelphia on July 1, 1874. They accepted an offer of candy from two men in a horse-drawn carriage and climbed in with them. (The parental admonition not to take candy from strangers is a legacy of the Charlie Ross kidnapping.) The men drove the boys out of town and then to the Philadelphia neighborhood of Kensington, where they let Walter out. Then they rode off with Charlie. Two days later his parents received a ransom note. “we is got him,” it said in broken English, “and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand. you will have to pay us before you git him.” The note demanded $20,000.

Two days later his parents received a ransom note. “we is got him,” it said in broken English, “and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand. you will have to pay us before you git him.” The note demanded $20,000.

That was a first.

America’s first kidnapping for ransom

No criminal had ever demanded ransom in an American kidnapping before. The novelty struck terror in the nation’s heart because it highlighted the vulnerability of its children. Parents feared losing their children more than losing their president. Following Charlie’s kidnapping, Pennsylvania became the first state to make child-snatching a felony. It had only been a misdemeanor when Charlie was snatched.

The legal change came too late to help Charlie. Although the police made some inroads in investigating the case, they never found the boy. You can read more about Charlie’s kidnapping in Carrie Hagen’s fascinating book, “we is got him: The Kidnapping That Changed America (New York: Overlook Press, 2011).

Charlie’s case had one unforeseen effect in the history of burglar alarms. Because the Van Brunt burglary was inextricably entwined with both the novel burglar alarm and a nationally publicized kidnapping, Edwin Holmes received a wave of free publicity for his new product. As newspapers all over the country reported the burglary and confession, readers devoured the story of the burglar alarm and its effectiveness. This was the first case to give the burglar alarm major publicity.

A twist of fate linked the first kidnapping for ransom with the history of burglar alarms. Burglar alarms are still with us. But except for the parental admonition not to take candy from strangers, Charlie Ross has been largely forgotten.

Literature on point:

“Back to Basics: Where Did the Burglar Alarm Come From?” Vintech (2011).

Fass, Paula. Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America (Oxford Univ. Press, 1997).

Hagen, Carrie. “The Story Behind the First Ransom Note in American History,” Smithsonian.com (Dec. 9, 2013).

Hagen, Carrie. we is got him: The Kidnapping That Changed America (New York: Overlook Press, 2011).

Lee, Seungmug, “The Impact of Home Burglar Alarm Systems on Residential Burglaries.” Ph.D. diss., Rutgers University, 2008, ProQuest 3326964.

International Foundation for Protection Officers. The Professional Protection Officer: Practical Security Strategies and Emerging Trends (Elsevier, 2010).

Ross, Nick. Crime: How to Solve It – And Why So Much of What We’ve Been Told is Wrong (Biteback Publishing, 2013)

“The Mystery Solved. The Abductors of Charlie Ross,” Indiana State Sentinel, 22 December 1874.

As always, an interesting and informative exploration of significant but little known events and their ramifications. Well done!

Thanks, James. It’s fun to explore two 19th-century crimes and find how they worked together to inform the public about burglar alarms.

Hi Ann Marie

I’ve done quite a bit of research on Holmes and I have published articles in trade periodicals about him. I was familiar with the story of the Ross kidnapping; however, you bring more insight to what I had previously read. Holmes was very much a marketer and used every opportunity to both market his product and protect his patent.

One correction – Augustus Russell Pope was the Unitarian minister who patented the electric burglar alarm. He was a Harvard educated theologian born around 1819. He discovered that he was sick with Typhus and sold his patent to Holmes before he died in order to provide for his family. Albert Augustus Pope (no relation to my knowledge) was a Civil War veteran who found success in the bicycle business. He was born in or around 1842.

Great article – very interesting!

Thanks for commenting, John, and I’m glad you liked the post. I can’t recall at the moment where I got my information about Pope and Holmes, but am grateful for anyone who can offer corrections or additional information. Knowledge, after all, is often a collaborative effort.