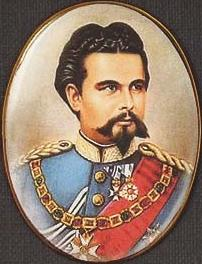

Germany’s Greatest Unsolved Mystery We know him as the “Fairy Tale King” and the “Swan King.” Some also call the “mad king of Bavaria,” but psychiatrists today debate whether he really was insane. He was the patron of Richard Wagner and the builder...

The Mississippi as the key to commerce Even if the Civil War never happened, and even if Robert E. Lee never became president of Washington and Lee University, we would still probably know him today. He changed American history not only as a general...

A whale sinks the Essex Directly towards the ship the sperm whale came, its tail churning the water and its body casting off a wake. As its massive head struck the port side of the Essex, the 87-foot-long whaleship shuddered, oak timbers splintered...

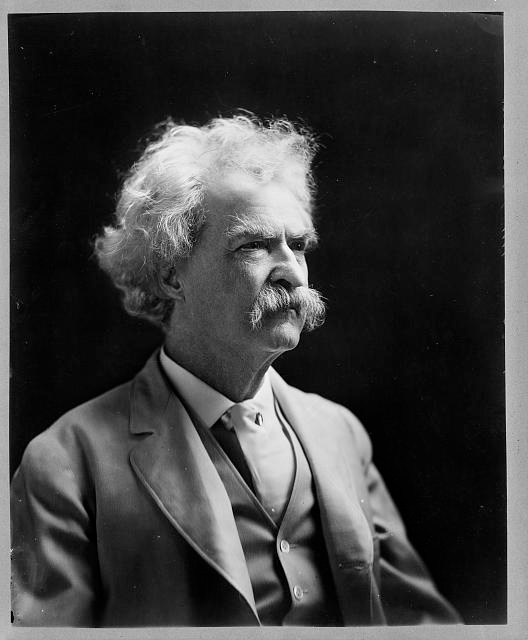

It can happen to anybody. Mark Twain had started several new books when it struck in 1878. His solution to writer’s block might surprise you. And the results probably surprised him. Mark Twain in Heidelberg Twain decided a change of scenery would...

Recent Comments