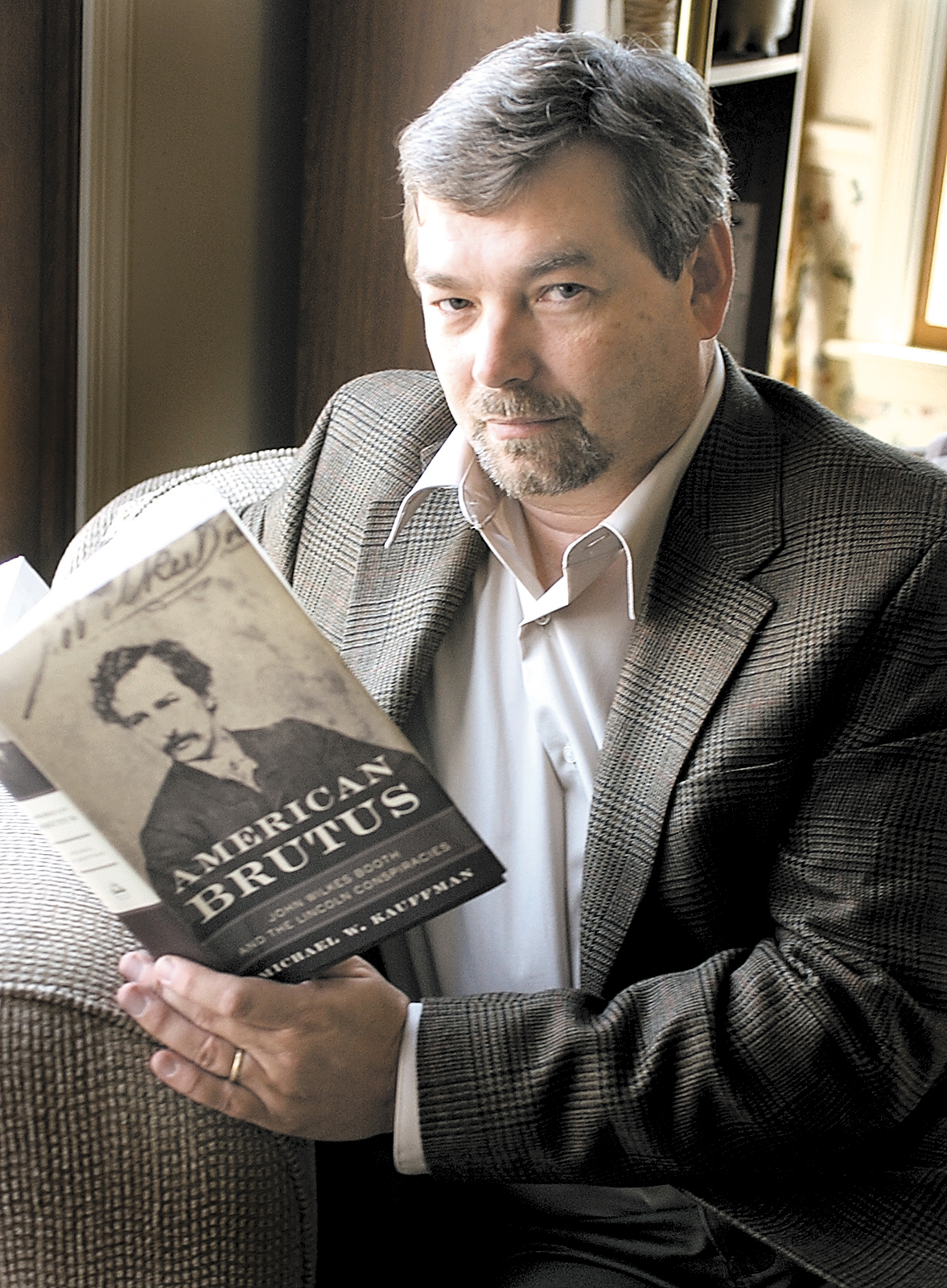

No, John Wilkes Booth did not break his leg jumping from the balcony after he shot Abraham Lincoln. He probably didn’t even hurt himself. At least not then. New insights into the Lincoln assassination don’t necessarily require the discovery of...

Cadaver dog teams break missing persons’ cases Finding the body provides crucial evidence in a missing persons’ case. Was it a natural death or a murder? If the former, the find helps bring closure to the family of the deceased. If the...

Pull away, me lads o’ the Cardiff Rose And hoist the Jolly Roger Roger McGuinn’s song was the pirate song I grew up with. And the Jolly Roger – the skull and crossbones against a black background – still waves supreme over American pirate lore...

Recent Comments