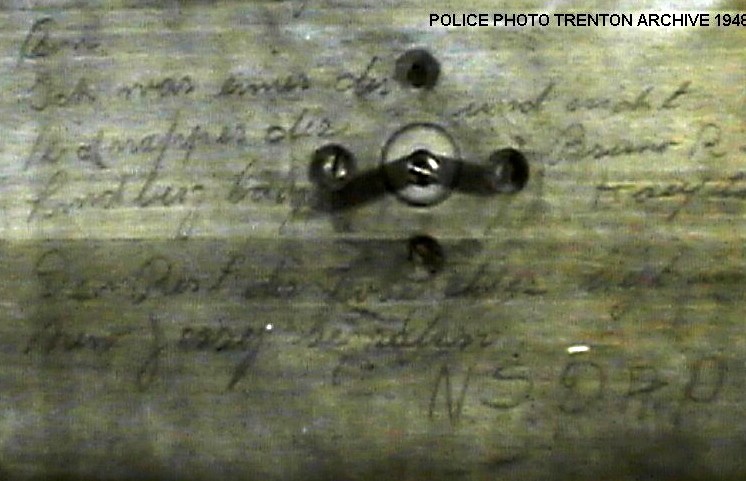

Certainly the oddest – and most recent – piece of evidence in the Lindbergh kidnapping is the “table block confession.” Last week attorney Richard Cahill, author of the new book Hauptmann’s Ladder: A Step-by-Step Analysis of the Lindbergh...

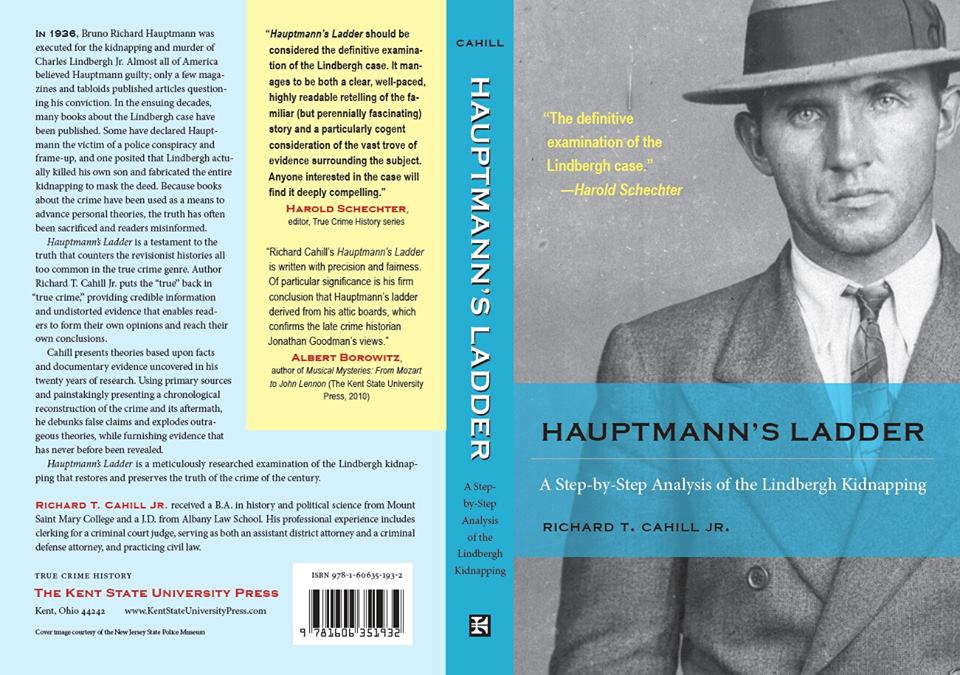

One of the most fascinating cases of the 20th century is the Lindbergh kidnapping. Eighty years later, experts still can’t agree if Bruno Richard Hauptmann was guilty of the kidnapping and death of Lindbergh’s son. And that confusion stems from the...

Interview with Author and Cadaver Dog Handler Cat Warren CAT WARREN is a professor and former journalist with a somewhat unorthodox hobby: she works with cadaver dogs—dogs who search for missing and presumed-dead people. What started as a way to...

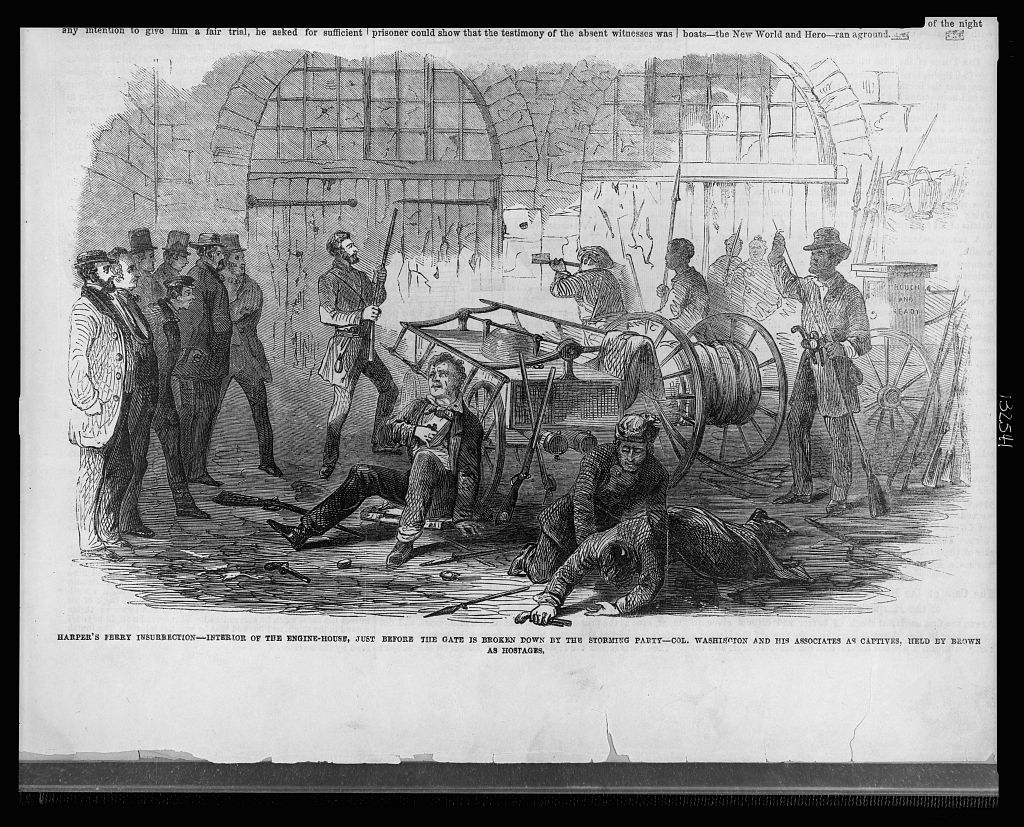

More than any other event, it was John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry that lit the fuse of North-South tension and ignited the Civil War. Brown planned the raid for two years in advance, so it was no mistake that the first thing he did when he...

Recent Comments