Every medieval town had its mysteries. Dilsberg, a walled town atop a hill that towers above Germany’s Neckar River, was no exception. Its mystery was its defense. Dilsberg had never been conquered in a siege, and the besiegers could never figure...

A black shape emerges from the misty shadows of the night and slinks up to the door. A glint of light flashes from a knife. There’s a scratching sound as the man begins to whittle a symbol into the wood. You probably won’t be able to...

Gespräch mit Michael Müller, einem der ersten Leichensuchhundführer in Deutschland (Deutscher Text unten) One month ago I interviewed Cat Warren, an American cadaver dog handler in America whose book, What the Dog Knows, has since hit the bestseller...

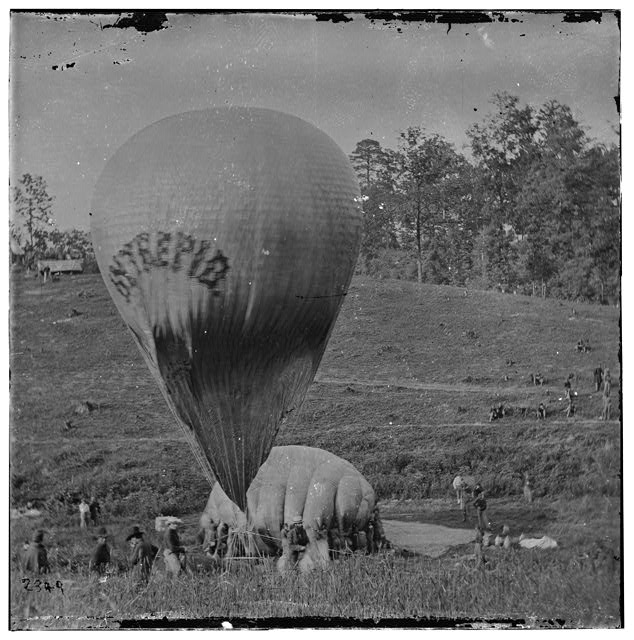

Spycraft rose to new levels during the Civil War. One of the most interesting innovations was ballooning. These five fun facts provide a brief introduction to what was then cutting edge military technology. Civil War balloons were not the...

A birch broom, fastened to a post, stands sentinel before a farmhouse in Germany’s vineyards. Red and yellow ribbons flutter from its handle. A board, bearing a hand-painted arrow pointing up the driveway, dangles below the broom. Vintner’s bushes...

Recent Comments