It’s perhaps fitting that one of the most controversial hearsay exceptions was first used in one of the most controversial trials of United States history. The muskets the British soldiers fired in the Boston Massacre found their marks in American...

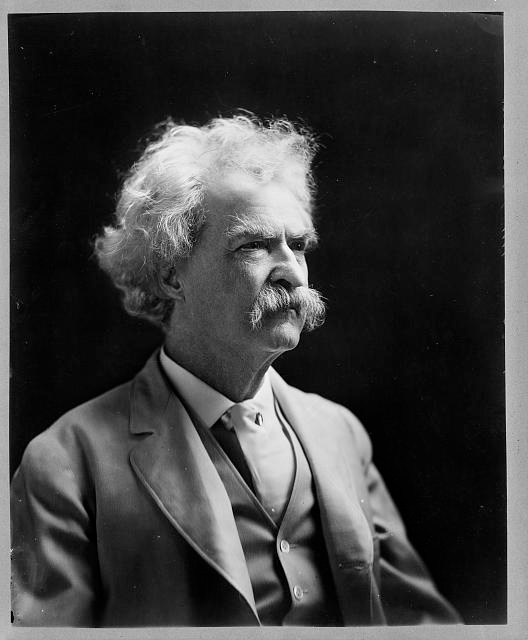

He put up a fine luncheon for us and added to it a quantity of great light-green plums, the pleasantest fruit in Germany…. Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad Greengages Anna Pavord, writing for the British newspaper Independent, calls them “most...

God! how delicious the memory of it!—I caught him escaping from his grave, and thrust him back into it. – Mark Twain, “A Dying Man’s Confession,” in Life on the Mississippi Murder and revenge. These two themes form the warp and weft in “A...

Recent Comments