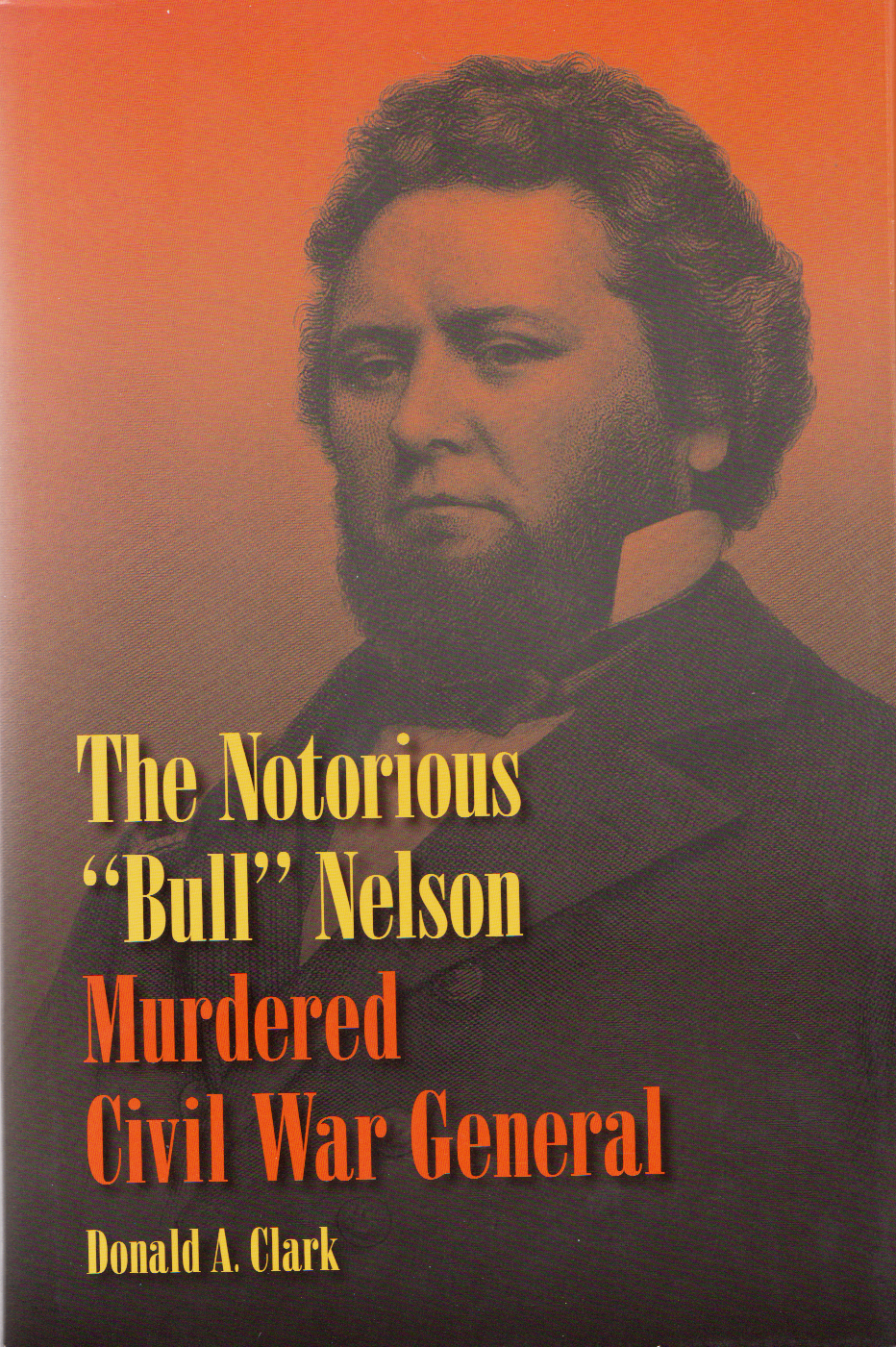

Part One: The Victim Not all bullets in the Civil War were exchanged between North and South. One of the most spectacular crimes of the Civil War, besides the Lincoln assassination, was the murder of Major General Bull Nelson from Kentucky. A fellow...

Dogs love stench. They are attracted to different fragrances than we are. They poke in garbage, sniff rear ends, and flop down on the beach to roll in dead fish. So it is not surprising that incidents of dogs discovering homicide victims sprinkle...

Why is Friedrich Schiller called the father of the modern true crime story in Germany? It’s because his debut crime story changed the genre. Schiller shifted the focus from sensationalism to motive. Here’s the tale in a nutshell. Christian Wolf,*...

Murder mystery authors harbor a secret they don’t want you to know. I won’t exactly tell you the secret (it would spoil mystery books for you forever after), but I can tell you a bit about the theory behind it. At a writers’ conference for murder...

In Spain and Slovenia, it’s an ivy bush. In France, a bundle of straw. Austria and Italy hang out pine branches and Germany and Switzerland birch brooms. You’ll often find them out in the country, dangling sentinel before a farmhouse. The vintner’s...

Recent Comments