A royal funeral makes criminal history

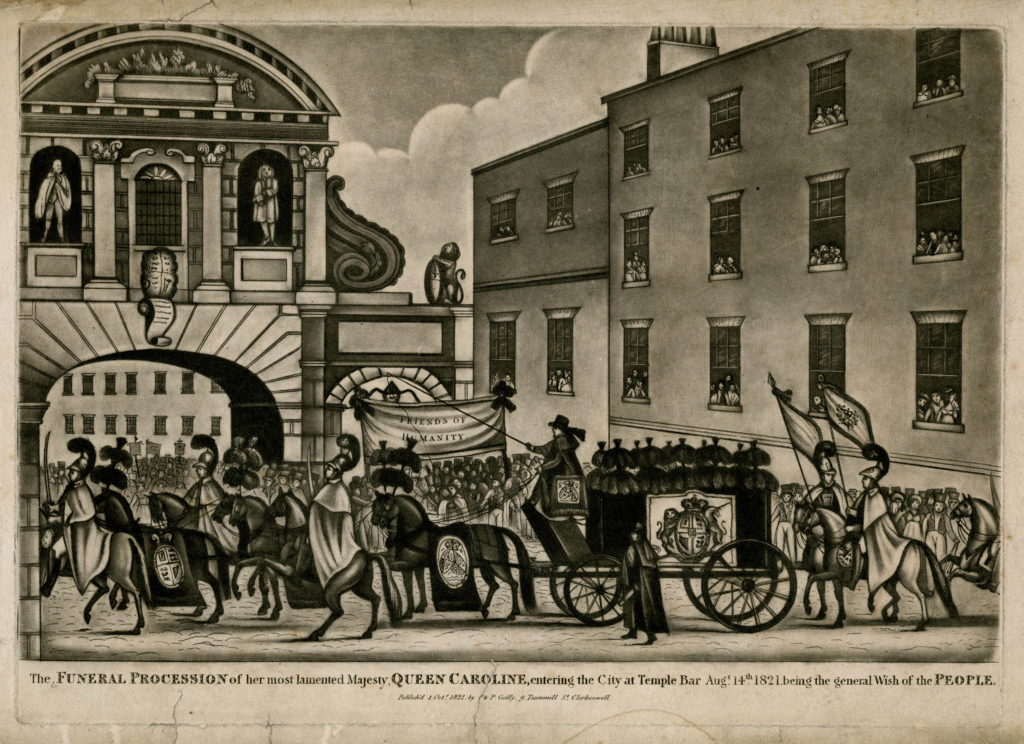

Black plumes bounced on the horses’ heads as they pulled the hearse through the rain and mud. The muffled hoofbeats foreshadowed change. Neither horse nor guard nor mourner could know the path before them led into criminal history, but it did. The reaction to Queen Caroline’s funeral procession became the origin of the police lineup.

Thirteen mourning carriages and the Life Guards, who had orders to escort the queen’s body, accompanied the hearse. Their route deviated from the normal royal funeral: Instead of going into the city center, the procession was to skirt the center and go around it. Ever since Caroline of Bruswick’s death a week ago, on August 7, 1821, officials feared the public would riot at her funeral procession.

And they were right.

But what they couldn’t foresee was how the procession would lead to an innovation in criminal procedure. Just one week later, London would stage an event that became the origin of the police lineup – with the Life Guards as suspects.

Lineups and showups

Police lineups – or identification parades, as they are known in the UK – have long been part of law enforcement’s tool kit for identifying suspects. But the origin of the police lineup is a bit murky.

The Baltimore Police Department has been using lineups for over sixty years. They’ve been part of British criminal procedure for much longer. An 1874 memorandum to the Home Office claimed the Metropolitan Police had used them since its inception. The earliest known police order for the regular use of the lineup was in 1860. Several court cases document lineups outside of London already in the 1850s.

Law enforcement developed lineups in response to criticism about the lineup’s older cousin, the showup. In a showup, the police apprehend a suspect matching a witness’s description, typically not long after taking the initial police report. The police bring the suspect back to the witness for an eyewitness identification: Was this person the perpetrator or not?

False identifications

Showups, however, can lead to false identifications. The problem is suggestiveness. Because the police are showing only one suspect, witnesses might have tendency to pick that one out.

Misidentifications weren’t just a modern concern. Even in the 19th century, scholars discussed the danger. William Wills listed several cases on misidentification in his 1838 essay on circumstantial evidence.

Origin of the police lineup

When the British police first started regular lineups, they might have been thinking of the example of the Life Guards at Queen Caroline’s funeral. Caroline had a controversial career as queen consort, yet remained very popular with the people. The city folk, angry that her funeral procession wasn’t supposed to head downtown, decided to force it. People set up barricades along the route to detour the procession where they wanted it to go.

When the Life Guards encountered a set of barricades, a riot broke out. The crowd pelted the guards with rocks and injured several of the troops. With orders to use their weapons to disperse the rioters, the guards shot and slashed a path through the people. Two men in the crowd were killed.

One week later, on August 21, 1821, witnesses gathered at the barracks to identify which guards had been shooting. The regiment lined up in formation. Under the supervision of the Bow Street magistrates (an early police force), the witnesses walked through the troops’ ranks to study their faces. Their identifications and testimony were recorded in the inquest proceedings.

Edward Higgs calls the inquest proceedings at the Life Guard barracks one of the first recorded instances of an identification parade. In the UK at least, Queen Caroline’s funeral procession case played an important role in the origin of the police lineup.

But the idea of the lineup was much older. It may have come from France, and interestingly, that case also had a royal connection.

A controversial French showup

One of the greatest criminal scandals in the reign of Louis XIV was a vast network of poisoners. Between 1679 and 1680, French police arrested over 400 suspects for crimes related to poisoning and black magic. Witnesses alleged that the web of conspirators reached all the way to the king’s court – with the king himself, in once instance, as the intended victim.

Claude de Vin des Oeillets, the king’s former lover and once a member of his court, found herself facing accusations. And she thought she had a brilliant way of proving herself innocent. Her accusers were jailed in the dungeon of Vincennes. Why not take me there, she asked her interrogator, and show me to them? Oeillets swore none of her accusers would even recognize her.

Her plan backfired.

Investigators brought her down to a room near the dungeon and had the guards bring the witnesses in. Two identified her immediately.

Argument for the world’s first police lineup

Oiellets’s showup procedure reaped criticism. One of Louis’s ministers, Jean Baptiste Colbert, attacked the showup as prejudicial. Because she was the only person presented to the witnesses, Colbert said, it would have been too easy for the witnesses to guess who Oeillets was. Colbert said they should have shown her with four or five other people.

That is quite a modern argument! What Colbert was actually demanding was the world’s first police lineup.

So if France is not the birthplace of the lineup itself, it still might be the origin of the police lineup with respect to its philosophical underpinnings. And that’s fitting, because France also gave birth to the true crime genre.

Literature on point

John Adolphus, The Last Days, Death, Funeral Obsequies, &c of Her Late Majesty Caroline (London: Jones & Co., 1822).

Frederick H. Bealefeld, “Research and Reality: Better Understanding the Debate between Sequential and Simultaneous Photo Arrays,” University of Baltimore Law Review 42(3):513-534, 519 (2013).

David Bentley, English Criminal Justice in the 19th Century (London: Hambledon Press, 1998).

Rt. Hon. Lord Devlin (1976). Report to the Secretary of State fort he Home Department of the Departmental Committee on Evidence of Identification in Criminal Cases. HMSO.

Edward Higgs, Identifying the English: A History of Personal Identification 1500 to the Present (London: Continuum, 2011).

Holly Tucker, City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First POlice Chief of Paris (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017).

William Wills, An Essay on the Rationale of Circumstantial Evidence (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans; 1838).

I didn’t know that about her funeral procession.

The Londoners were probably more ticked off that the route violated some ancient privilege if theirs than for any affection for the queen. They had cheered her and supported her during the divorce trial and scorned her during the coronation.

I would think it would be hard to identify a few men in uniform out of a large force of them. Surprised any one cared who shot the men unless the charge was they did so without reading the riot act. very good blog as usual.

Thanks for your comment, Nancy. I was a bit surprised too that the London police went so far investigating the shooting incident. They could have just made the argument that the shooting was justified in face of the riot. I didn’t follow through on my reading on whether any of the guards were tried and convicted, but if you want to read an original source, I’d refer you to the John Adolphus source. It’s online and I’ve linked to it. A description of the lineup — from the perspective of an inquest juror who was present but wasn’t allowed to watch it — starts on p. 188.

There had to be an inquest on the dead man– according to the report by Adolphus. Quarrelsome and much animosity between the coroner’s jury and the military. The dead man was shot by an unknown military man, according to the inquest. Several witnesses did mention that they didn’t hear any one read or mention the riot act.

Yes, it was an inquest on the dead man. And it was having the witnesses view the Life Guards that made this case so unique. Interesting reading, isn’t it?

I know that it has been a few years, but just so that you know, the guards were not convicted on a technicality. Hope that was helpful to you.

( See Higgs, E., (2011). Identifying the English. London: Continuum, p. 128.)

Thanks for the information, Kym. Do you mean that they weren’t convicted at all or that they were convicted, but it was based on a substantive reason and not a technicality?

Hey! I´m doing an essay for school abouth the line-ups in the US, i would love to use this information and of course cite the page in the literature but I feel compelled to ask what are the sources of this publication, only for issues of veracity

The sources for my information are listed in the “Literature on Point” section at the end of the post. I’d be honored if you could use some of my information in your essay. Thanks for commenting, Andrea.

Hello, I am a retired Metropolitan DC Police detective. I also teach legal and investigative psychology at a local university. I am curious about the information about current police line-ups. Has your research determined that agencies are still conducting “live” police line-ups as a regular method of identifying suspects of offenses? I believe most departments switched from “live” type line-ups to photo-line-ups some years ago. I suppose it can also be called a photo-line-up, but I wanted to make sure you recognized the difference between current photo-line-up and the older method of “live” line-ups. If I am wrong, I would appreciate your research findings on which agencies are still using “Live” line-ups as a regular method of identification of suspects. You mentioned Baltimore in the article, but I found no information that Baltimore was doing anything different in that respect to DC Metropolitan Police. Thank you in ADVANCE!

Thanks for commenting, Tim. The short answer is, I don’t know. I used to practice criminal law in the United States, but I have since moved to Europe and am no longer familiar with current practices. At the time I practiced, yes, live line-ups were still being used. To answer your question, I’d have to do some research. But either way, this story is part of history.