Historians are a bit like detectives. They sift through evidence, weigh it, and try to leave no stone unturned. But when they publish their results, they’re a bit like lawyers. They need to be objective enough to gain the credibility of the judge...

An Interview with Author Kim Murphy Every once in a while, a book comes along that shifts the tectonic plates in my understanding of history. I used to practice law and was the prosecutor for parole revocation hearings in a ten-country region...

No history of a war is complete if it focuses solely on men. Women’s experiences, at home and on the battlefield, shaped the postbellum world. Women, perhaps more than men, held society together during the war and rebuilt it afterwards. Giselle...

Might one crime have influenced the course of the Civil War? Yes, according to one researcher. The 1864 Gold Hoax blew a cannon ball through Lincoln’s efforts to build up the Union troops. It also highlights one of the strangest coincidences in the...

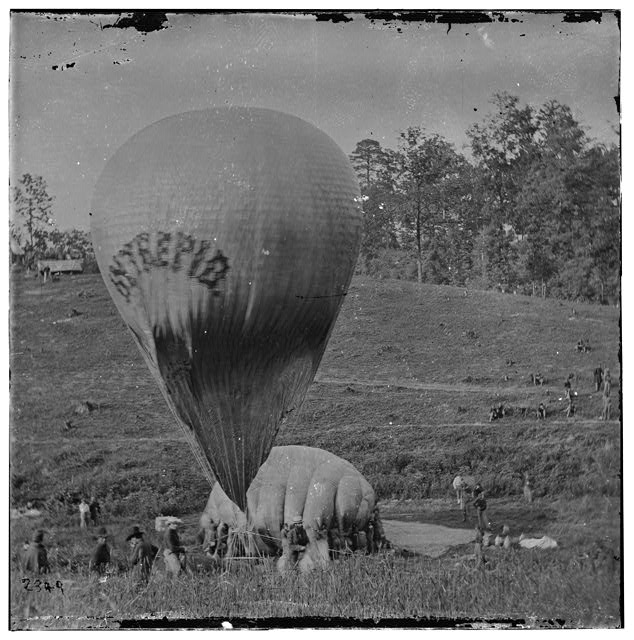

Spycraft rose to new levels during the Civil War. One of the most interesting innovations was ballooning. These five fun facts provide a brief introduction to what was then cutting edge military technology. Civil War balloons were not the...

Recent Comments