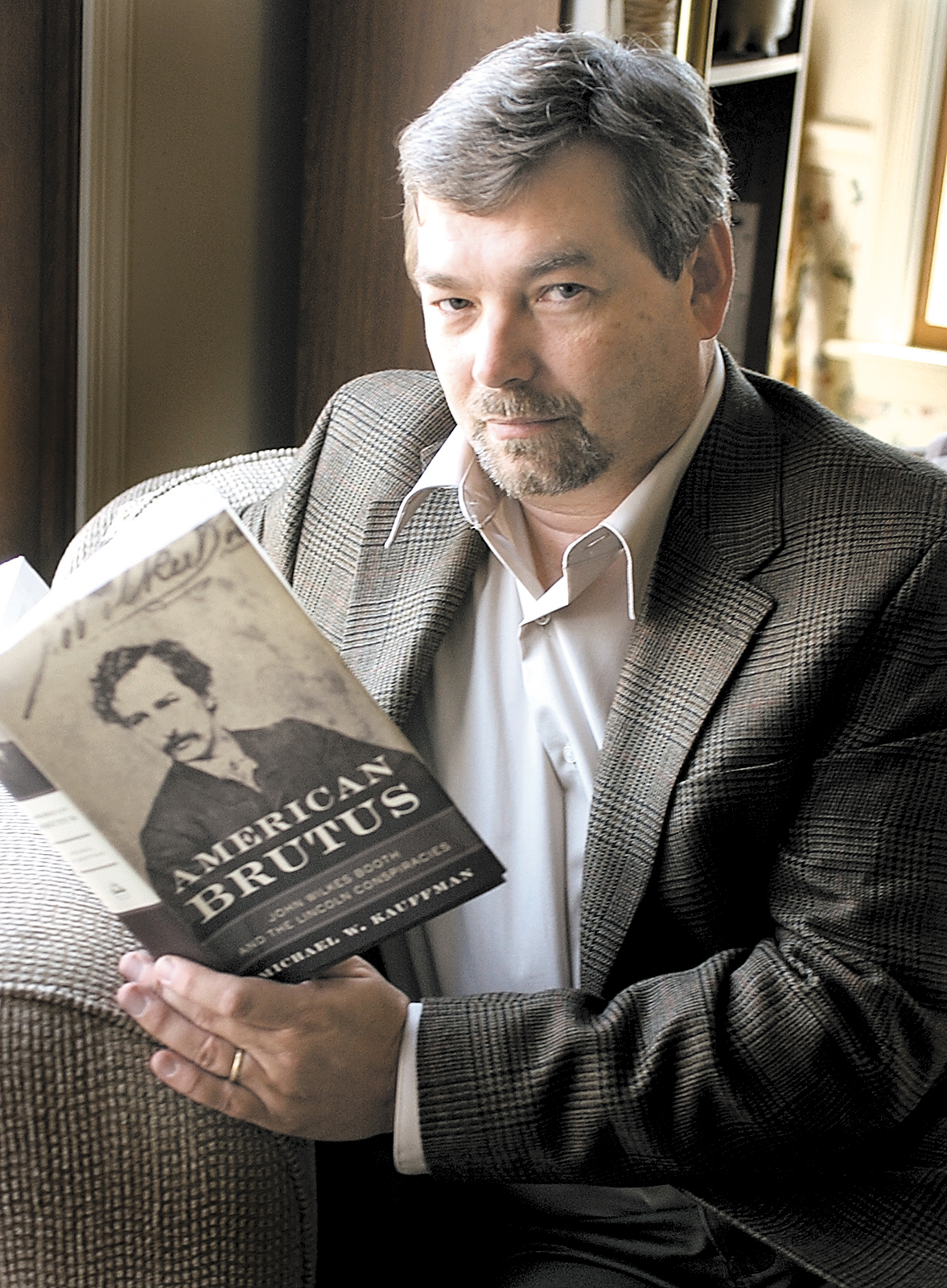

What happened to the man who shot John Wilkes Booth? One of the lingering mysteries of the Lincoln assassination concerns Boston Corbett, the man who shot John Wilkes Booth. In 1888, Corbett disappeared into thin air. Michael W. Kauffman, a Lincoln...

No, John Wilkes Booth did not break his leg jumping from the balcony after he shot Abraham Lincoln. He probably didn’t even hurt himself. At least not then. New insights into the Lincoln assassination don’t necessarily require the discovery of...

Recent Comments