They are Germany’s most famous stuffed animals, at least for Americans. A snowy owl and a wildcat lurk in the taxidermy display cases of the Langbein Museum in Hirschhorn, Germany. They’re renowned because Mark Twain wrote about them in A Tramp...

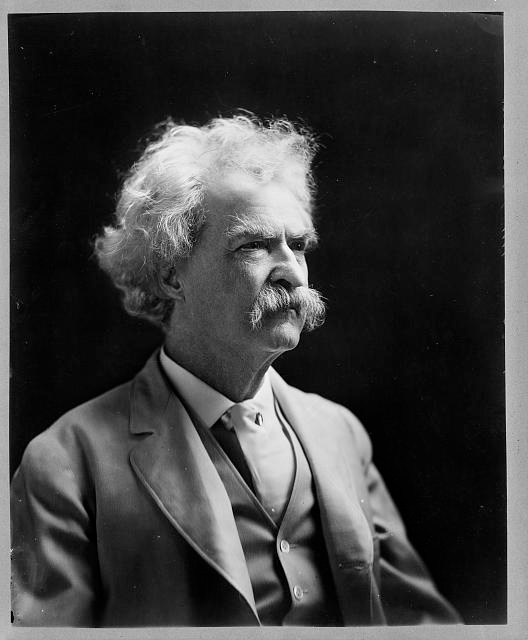

It can happen to anybody. Mark Twain had started several new books when it struck in 1878. His solution to writer’s block might surprise you. And the results probably surprised him. Mark Twain in Heidelberg Twain decided a change of scenery would...

Recent Comments