Anatomy of a No-Body Murder Case This was a prosecutor’s nightmare. Jessica O’Grady’s made her last cell phone call to her friend Keri Peterson at 11:29 pm on May 10, 2006 in Omaha, Nebraska. The 19-year old was near her boyfriend’s home. At 11:48...

Many U.S. presidents came from a military background. Abraham Lincoln was no exception. His brief service as both a captain and a spy in the Black Hawk War was unusual. But it offered some training for his future political life. As far as I know...

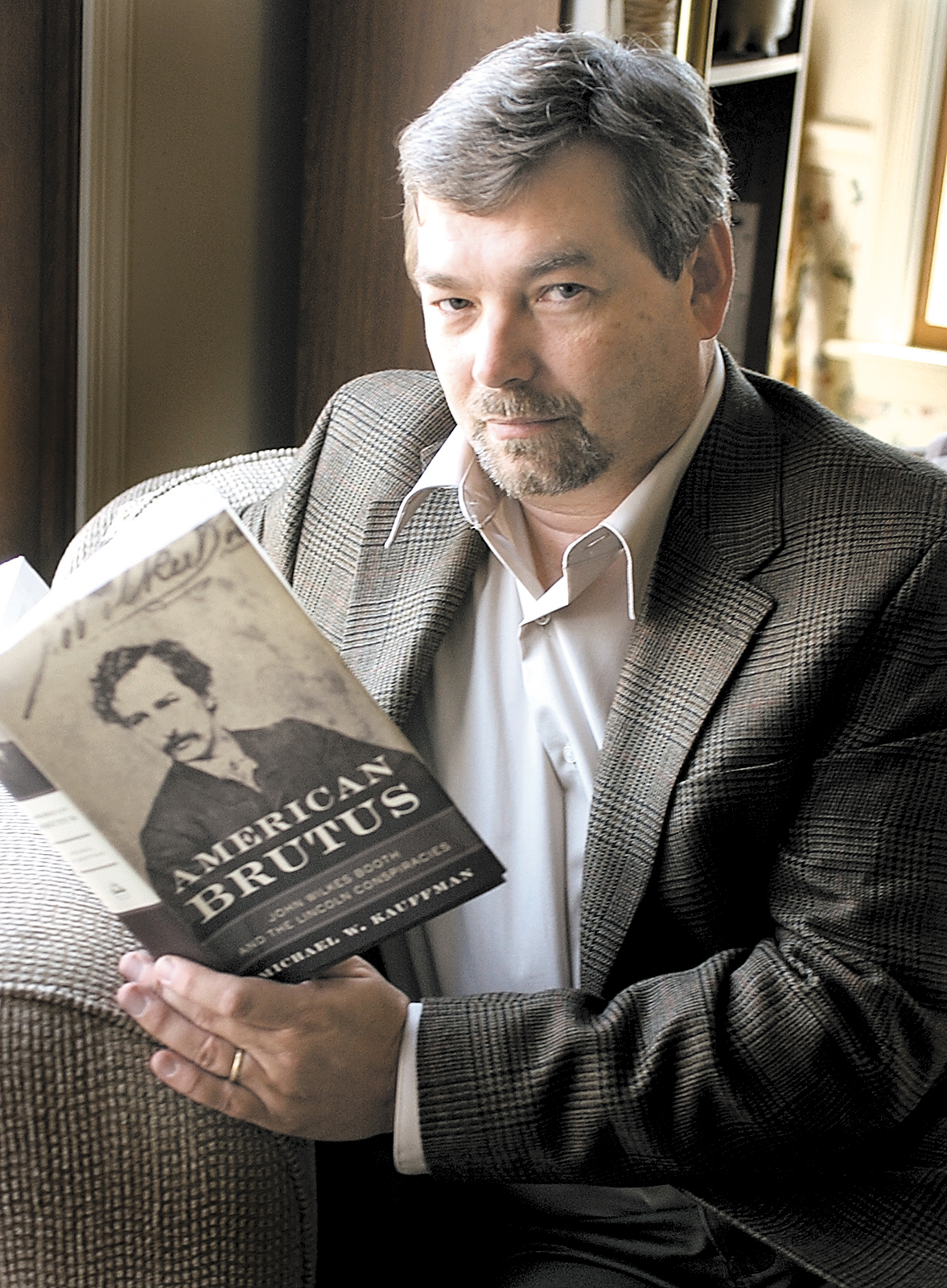

No, John Wilkes Booth did not break his leg jumping from the balcony after he shot Abraham Lincoln. He probably didn’t even hurt himself. At least not then. New insights into the Lincoln assassination don’t necessarily require the discovery of...

Who knew? Abraham Lincoln picked up his pen not only to scratch out the Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural Address. He also wrote poetry and true crime. His one true crime short story, published in the Quincy Whig in April 1846, is based on a...

Recent Comments