On May 19, the Gaithersburg Book Festival will witness a world true crime record being broken when a German mayor pays a 146-year-old reward for solving a murder of his predecessor in 1835. It will go to the American descendants of the man who cracked the case in 1872.

That will be only the last of the records this case has broken. The murder, detailed in the award-winning book Death of an Assassin, also made history for these records:

- 19th-century Germany’s coldest case ever solved, with 37 years between the murder and solution

- Its only murder solved in America outside of a confession

- The birth of forensic ballistics, which was first used in this case

Swenson Book Development recently interviewed me about Death of an Assassin and graciously gave me permission to reblog it on my site.

The Case That Spanned an Ocean – An Interview with Ann Marie Ackermann

Audrey Schultz | April 17, 2018

Originally posted on the Swenson Book Development Website

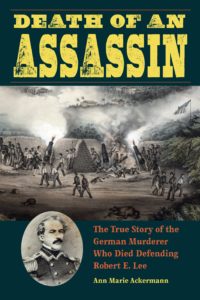

If you’re a history lover or a fan of good mysteries, then Ann Marie Ackermann’s novel Death of an Assassin: The True Story of the German Murderer Who Died Defending Robert E. Lee is the book for you. This historical true crime novel details the story of a case that breaks several records, including coldest case ever solved, and intertwines both German and American history. Now, in large part because of the novel and its author Ann Marie Ackermann, another record is set to be broken next month in Gaithersburg, Maryland: the oldest reward for solving a murder case ever paid.

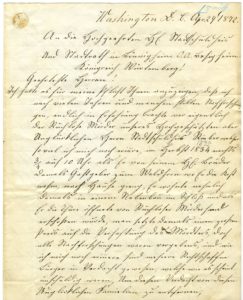

May 19 at the Gaithersburg Book Festival, Ann Marie Ackermann, accompanied by the current mayor of Bönnigheim, Germany, Kornelius Bamberger (pictured above), and Gaithersburg Mayor and Book Festival Founder Jud Ashman, will present the 146-year-old reward to the descendants of the man who provided the tip that solved the case. As explained on the Gaithersburg Book Festival website, “Frederick Rupp, a German immigrant in Washington, D.C., provided the crucial tip in 1872 that solved the murder, but the reward was never paid after the city council minutes recording the decision to offer the prize were misfiled and archived.”

Death of an Assassin has been awarded a bronze IPPY for the True Crime category. Conducted annually by the Independent Book Publisher Awards, the IPPY honors the best independently published titles from around the world. Congratulations to Ann Marie Ackermann.

In light of all this exciting news, I had the chance to interview Ann Marie Ackermann for Swenson Book Development, and I am thrilled to share it with you.

Swenson Book Development: What was your favorite part about writing this historical true crime story?

Ann Marie Ackermann: The discoveries I unearthed in the archives just floored me. When I first started researching, I thought I was just going to write a about a small-town murder for my local German historical society in Bönnigheim. But the case was so much bigger than anyone thought. This was 19th-century Germany’s coldest case ever solved and its only case solved in the USA: A German immigrant in Washington, DC provided the decisive tip 37 years later. I tracked the assassin’s flight to the United States to escape justice in Germany, only to discover that Robert E. Lee had written a letter about him without knowing his past history of crime. Lee’s praise turned the assassin into a symbol of the costs of the Mexican-American War, but his identity has been a mystery to Americans. So this case solves mysteries on both sides of the Atlantic!

SBD: Extensive research went into writing Death of an Assassin. What did your research process look like?

AMA: I spent loads of time in the German archives and needed to learn to read the old German handwriting. The archivists were extremely helpful.

I did fly twice to Philadelphia to visit the archives there, but ended up hiring Gail McCormick, a talented Washington, DC archivist, to help me with research at the National Archives and Library of Congress. It was just too expensive for me to fly over the ocean every time I had a question. The material she found helped identify the German assassin as the object of Lee’s admiration.

SBD: How did your experience as an attorney with a focus on criminal and medical law come into play while writing this book?

AMA: Two things shape a criminal investigation: the law of criminal procedure and the forensic technology available to the detective. Those two aspects guided me in my research and analysis. And they bore fruit: I was able to show that the detective in this case was the first to use forensic ballistics. That’s another record right there!

My background in medical law gave me lots of experience reading autopsy reports, so it was really fun to read one from 1835. A cardiologist friend of mine helped me pick it apart and put it under the microscope of modern medicine. In some ways the doctors in 1835 were surprisingly modern; other aspects of their practice were oh-so-quaint.

SBD: What would you say was your biggest obstacle in writing and researching for Death of an Assassin?

AMA: Learning to read the old German handwriting! I’m so glad I did, though, because it opened so many doors in my research. The investigative file in this case alone is almost 800 pages. I couldn’t rely on friends and archivists to read it for me. When I got to the point I could read it myself, I unearthed so many interesting aspects of the case.

SBD: One of the things I enjoyed most about your book was getting to read from the perspective of historical characters, particularly Robert E. Lee, which made history come alive for me as a reader. What was it like as an author delving into the minds of historical characters like Robert E. Lee?

AMA: I’m so glad my book brought history alive for you! My hope, in writing Death of an Assassin, was that the true crime format would get some people reading about past events who wouldn’t otherwise have been interested. And from the feedback I’ve been getting from readers, it sounds like I reached that goal.

To delve into the minds of historical characters, I tried to use as many primary sources as possible. What did they themselves write about the events? And what did the people who were with them have to say? I tried to use that technique not only to put the reader into a historical character’s mind, but also to place the reader in the din of the battle scene at the climax of the book.

I also wanted to show there’s more to Robert E. Lee than just the Civil War. Even if the United States had never fought the Civil War, history books would still remember Lee for his accomplishments in opening the St. Louis harbor and in the Mexican-American War. Because the Civil War overshadows those parts of American history, they’re somewhat obscured. My research taught me new things about that period, and if this story opens people’s eyes to broader aspects of antebellum history, I’d be pleased.

SBD: You moved from the United States to Germany in 1996. What was the transition like? How is life in Germany different from life in the United States?

AMA: The transition wasn’t too difficult. I’m German-American, already had blood relatives here, spoke the language, and of course I had my German husband. I’d describe the transition as an adventure, but it was one that taught me what it means to be American. Living in another culture is like holding up a mirror to better see your own.

Wherever I live, I try to look for the positive aspects, and I’ve come to appreciate Germany for its excellent education and health care system. I’ve enjoyed raising my children here. But I miss the United States too.

SBD: Next month at the Gaithersburg Book Festival in Maryland, you get to present a long-lost reward to the American descendants of the man who provided the tip that solved this record-breaking case. What are you most looking forward to about this experience?

AMA: Payment of the 146-year-old reward will bring closure to this case and pull a 19th-century story right into the present.

The city of Bönnigheim is applying for a Guinness World Record title for the oldest reward for solving a murder ever paid. If Guinness grants the title, the town of Bönnigheim and I will be popping so many champagne bottles you’ll probably hear us over in the United States. What could be a better way to draw a spotlight onto the town and my book? It’s an author’s dream, really, and I’m so glad my legwork on the reward is coming to fruition. I’ve been working a couple of years to make the reward happen.

Now I’m most looking forward to meeting the descendants – the flesh and blood embodiments of one of the characters I wrote about. They will be the focal point of the ceremony in Gaithersburg, and if they ever decide to visit Bönnigheim, they’ll be received as the descendants of a town hero.

SBD: What are your writing plans for the future?

AMA: So many Germans want to read this book too. Before I tackle a new project, I’m going to be assisting with the translation.

After that I have a couple of ideas in mind – more historical true crime in Germany, and a history of a European food and wine tradition that dates back to the Romans. I’d love to visit all the European countries that still follow the tradition, taste their wares, and put together a coffee table-like book of a pan-European custom.

Oh, and my kid still wants me to publish the bedtime stories I told him as a child. So there are lots of ideas.

Image credits:

1. Bürgermeister (Mayor) Kornelius Bamberger. Credit: Courtesy of the city of Bönnigheim, Germany.

2. Ann Marie Ackermann. Credit: Inge Hermann.

3. Death of an Assassin book cover. Credit: Kent State University

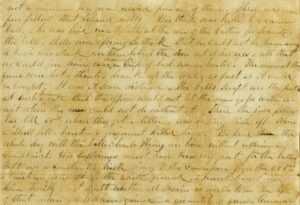

4. Detail of Robert E. Lee’s April 11, 1847 letter to his son, Custis. This section discusses the assassin from Bönnigheim. Courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society. deButts-Ely family papers.

5. Letter from Frederick Rupp with the tip that solved the case. Credit: Courtesy of Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, Branch Depository Ludwigsburg, Germany; StAL E 319 Bü 146.

What an amazing experience you have had in researching & writing this book Anne Marie.

I can just imagine how interesting it was to read and learn from Robert E Lee ‘s writings.

I can’t wait to read your book!

Thank you, Angelina! I hope you enjoy the book. You are right, I had a few jaw dropping experiences during the research. Who said archives are boring?

You are incorrect about the first time a bullet was matched to a firearm. That was a Bow Street Runner in 1835. In 1835 Henry Goddard (UK) of the early British Police force, the Bow Street Runners, became the first person to use the technique of bullet comparison to solve an active murder enquiry. When a woman known as Mrs Maxwell from Southampton, UK, was shot and killed in her home, her butler Joseph Randall claimed that an exchange of gunfire with burglars had taken place. However, when Goddard examined Randall’s gun and ammunition he identified an identical pimple on all the bullets found at the scene, including the ones that killed Mrs Maxwell and which Randall alleged were fired at him. Goddard found a corresponding pinhead-sized hole in the mould from which the bullets had been made, thus proving that the murder had been committed by Randell himself.

No, I’m not incorrect.

First, my book contains a lengthy discussion of Goddard’s 1835 case and why it’s not considered forensic ballistics. Goddard was able to match the imperfection on the handmade bullet to an imperfection in the butler’s bullet mold, but NOT to the butler’s firearm. It was a good piece of detective work, but not classic forensic ballistics. It’s what the German police — in reference to Goddard’s case — call a “Formspur” (mere physical evidence). Forensic ballistics looks at the marks a firearm leaves behind on a projectile, such as the striations on the surface of a bullet left by the grooves and lands of the rifling in the barrel, and attempts to identify or rule out a firearm by comparing the striations on the bullet used in the crime with the striations on a bullet that was test-fired from a suspect firearm. The German investigating magistrate Eduard Hammer was the first documented investigator to have done that.

Second, Eduard Hammer also conducted his investigation in 1835, so even if Goddard actually had used forensic ballistics, it would come down to the date. I have not been able to ascertain in what month Goddard did his investigation — do you know?

The archival discovery of Hammer’s use of forensic ballistics in 1835 is only a few years old, so you won’t find it in the classic works on the history of forensics. But Hammer’s achievement has now been acknowledged by the state police in Baden-Württemberg and by an article in a German law enforcement journal (Historischer Waffentest, pp. 9-10), in case you can read German. My hope is that with time, Hammer will gain the international recognition he deserves.