An Interview with Russian Historian

Margarita Nelipa

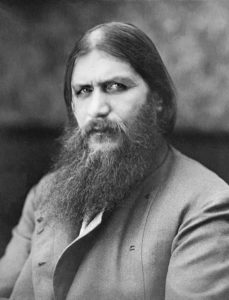

Grigorii Rasputin: Russian mystic, counselor to the imperial family, and murder victim. Apart from the execution of the Romanov family in July 1918, the murder of Rasputin in December 1916 is Russia’s most famous murder case. So famous, in fact, that his life is now celebrated in song and legend.

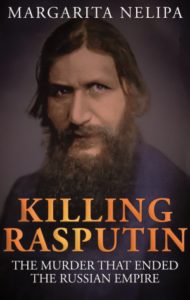

If there was ever a true crime author to tackle the Rasputin case, Margarita Nelipa is it. She can speak and read Russian fluently. She has both legal and medical training. She gained access to Russian files never before published in the West and used her training and experience to analyze Rasputin’s autopsy report. The result? A new book, Killing Rasputin, that offers Western readers information that’s never been published before in English. With over 1800 footnotes, mostly to primary sources, makes this one of the most academically grounded books on Rasputin.

What really happened to the Siberian strannik (religious pilgrim) who befriended the imperial family, sought to comfort the hemophiliac heir to the throne, Alexei, and was later found frozen and murdered in a river? Margarita Nelipa joins us for an interview and inserts her scalpel between truth and myth.

Interview with Margarita Nelipa

What information in your book Killing Rasputin hasn’t been published in English before?

Where do I begin? When you glance at the Bibliography and Endnotes sections at the back of the book, you will find that most of the references come from 100-year old Russian language sources. Few of those sources have been used in the West and fewer still cited in studies that focus on Grigorii Rasputin’s life. Since I approached Rasputin’s murder as a cold case, that circumstance alone sets my book apart from the standard biographies or crime thrillers published in Russia and in the West.

Living in Australia as a Russian historian is, as you can imagine, rather problematic as far as physically accessing documents. However, I overcame that sense of remoteness after firstly gaining access then visiting the Helsinki University Library as well as travelling to Russia to examine the two crime scenes just as the investigators had in 1916. Thanks to the freer publishing of books and the slow opening of the archives in post-communist Russia in addition to the internet, I was able to collect everything I needed. For this book, I accumulated a large volume of previously ignored material, which I drew together, translated what I needed, to reveal a multilayered story.

New biographical material

My book comprises three parts, the first being a biographic study that is followed up with the political and social events that brought together the co-conspirators who were directly involved in murdering Rasputin. Here I reveal several new facets of Rasputin’s life, which are accompanied with the first-time publication in the West of the photograph that shows (in part) Grigorii’s Birth Certificate and death notice. I am the first to verify that Rasputin first entered St. Peterburg in 1904. Another example of new material is my accessing of the Russian Orthodox Church’s secret Consistory Investigation (begun in 1907 and terminated in 1917) file. The panel of clerics who examined Grigorii Rasputin’s purported membership in the prohibited Khlyst sect – an accusation, I should point out here, that continues to be used against him to this day. Using the emperor and empress’ diaries and similar sources, I clarify the real nature of Rasputin’s association with the imperial family. From the published 1912 medical records and telegrams sent to the imperial (Alexander) palace, I introduced new information and at the same time, dispelled the popular notion that Rasputin’s alleged intervention was a spiritual happening.

New cold-case analysis

The second component involves my step-by-step investigation of the cold case murder; and the third part discusses the connection between Rasputin’s brutal murder and the advent of the February Revolution that follow, the Emperor’s abdication, and the ensuing collapse of the Empire. Few biographers have gone outside the books written by Rasputin’s murderers, Vladimir Purishkevich and Felix Yusupov. I believe that the widespread reliance upon those sources, masks the facts to a great degree, though to be fair, not all that they divulged, can be discounted as fiction. I am the first person to point out the similarities and differences as to how these co-conspirators “recalled” their participation in the murder on 16/17 December 1916. However, that stepping stone inspired me to piece together more probable scenarios. To achieve that objective, I waded through the accounts written by the principle investigators, including General Arkadii Koshko, the Head of Criminal Court Investigations in Russia in addition to that of the principle prosecutor from the Petrograd District Count, Sergei Zavadsky and the Chief of the Petrograd Okhrana, General Konstantin Globachev. Their recollections not only afforded a balance about the course of events but also added new perspectives to this murder case.

I was the first to publish the full of set 1916 police eye witness depositions, most of the police photographs related to the case (with application of my own descriptive inserts) and central to my thesis, the pathologist’s autopsy report.

New political analysis

Furthermore, to provide the political perspective that is entwined with this case, I used several key speeches that are to be found in the 1912 and 1916 Duma’s (akin to a Legislature) Stenographic Records – speeches that caused public opinion to turn against the imperial throne, the empress and by association, Rasputin. My use of newspaper and journal articles that were published in St. Petersburg (that was re-named Petrograd in 1914) during the early part of the twentieth century are also first-time inclusions.

I am the first person to translate and have published the statements of former imperial government personalities that were chronicled by Alexander Blok (the author) during the proceedings of the Provisional Government’s 1917 Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry. Numerous, diaries, letters and memoirs penned by key persons particularly those left by Grand Dukes Nikolai Mikhailovich and Andrei Vladimirovich are other sources that most historians in this field tend to overlook when it comes to writing about Rasputin. They revealed crucial information that proved that I was following the right path. It was Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich’s words that gave me the icing on the cake. Trained in law and along with his friendship with Victor Sereda, the special investigator at the Petrograd District Court, Andrei Vladimirovich revealed key forensic details that answered two questions. The Grand Duke described the bullet that was discharged and entered Rasputin’s back. It was also the only bullet that was recovered during the autopsy of Rasputin’s body. The significance of that bullet became apparent when I compared that information with the 1916 forensic photograph of Rasputin’s forehead. What I deduced is original work on my part. Giving scientific reasons in the book, I can reveal here that the bullet that passed through Rasputin’s forehead left a distinct measurable indentation that proved beyond doubt that a jacketed bullet was fired from a Russian weapon. My quest was complete. I had established that the recent eagerness to implicate a British agent firing his British military issued weapon was based on fiction.

“It has often been necessary for me … to conduct various difficult and unpleasant autopsies. I – am a person with strong nerves…, I have seen sights. But seldom did I have to experience such unpleasant moments, such as during this terrifying night.” – Professor Dmitri Kosorotov, the pathologist who conducted Rasputin’s autopsy, translated by Margarita Nelipa for Killing Rasputin

Does that information change traditional explanations of what happened to Rasputin?

Yes, it certainly does. By providing the translation of Professor Kosorotov’s published 1917 article, the reader will discover contradictions that dismiss the long-held myths that Rasputin was poisoned or had drowned. I can add that my photographic evaluations also dispel the myth that Rasputin was blessing himself prior to his death. My book explains why the murder was planned in the first place and once it was committed, what happened to his corpse. Few realize that not only was the corpse exhumed, but that it was cremated in the furnace that was located at the University that is located on the outskirts of Petrograd.

Most today believe that the three co-conspirators got away with their crime, however, given that few looked beyond the crime, they failed to see that the Emperor, as the final arbiter, did indeed use his autocratic authority to discipline both noble co-conspirators (Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and Felix Yusupov) to the extent the imperial criminal law allowed. This complex legalistic scenario may be read in the third component of the book. It fact I believe it goes a long way to solving why and how the crime was planned, who was involved behind the scenes as I define “the mastermind” and then finally committed by willing co-conspirators who happened to be of high standing in Russian society.

“Unconquerable, like a granite cliff” – Alexander Sprididovich

Just what did Rasputin mean to the Empress (Alexandra Fyodorovna)?

Rasputin was a semi-literate peasant who developed the ability to utter simple thoughts about life matters and preach his faith. It was his religious commitment in a manner not seen in St. Petersburg society and his knowledge concerning the scriptures that were factors which the pious empress valued most. Rasputin brought her piece of mind when most needed. Nevertheless, there was another aspect about Rasputin, which to my mind was uncomplimentary. He gave the empress the impression that he was able to alleviate her son’s periodic hemophilic episodes through the power of prayer.

Essentially, Rasputin caused her to accept him as her son’s savior especially following his near-death event in 1912. Except it must be said, this time the alleged healing happened vicariously by means of forwarding telegrams! Remarkably, people still credit this myth. The head of the Okhrana at the Alexander Palace, General Alexander Spiridovich described their association rather differently, whereby Alexandra Fyodorovna’s reliance on Rasputin was “unconquerable, like a granite cliff”.

“Ra ra Rasputin, lover of the Russian queen” – Boney M, Rasputin

Did they really have an affair like so many Russians hypothesized?

Absolutely not! Sadly, this wretched myth, as evaluated in my book was created by one person who wanted to disgrace Rasputin. This scandalous rumor was passed onto to the public to tarnish the dignity of the Russian empress and with that the Crown. Behind closed high society doors, the ensuing gossip was a treacherous matter! Yet, those, including the sovereign, who knew how the imperial court ran day-to-day remained silent. What the gossipers ignored was the fact that all visitors were under the surveillance of the palace security, no matter who they were. Rasputin and the empress were never alone together.

“No one has the right to commit murder” – Tsar Nikolai II

Several of the people involved in the murder were nobles. How did that hinder the investigation?

Since the sovereign was the only person who had the legal capacity to close the case, several members of the extended Romanov family including the sovereign’s mother, Dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna, pleaded for him to stop any action (Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich’s arrest and expected exile to Persia) simply because he was one of their own. Others in the extended family considered that Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich’s participation was “a patriotic act” and thus any form of punishment must not be considered. This term created by Grand Duchess Elizaveta Fyodorovna (then a nun and also the empress’ sister) may be read in the letter she sent to the sovereign.

Maintaining a wall of familial defiance, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich’s father, G. D. Pavel Alexandrovich (son of Alexander II) along with a group of other grand dukes confronted the sovereign face-to-face. Furthermore, sixteen Romanovs, co-signed a petition, pleading for compassion. In the meantime, Grand Duke Gavril Konstantinovich approached Justice Minister General-Procurator Nikolai Dobrovolskii so that he would view the matter “favorably” to “soften Dmitri’s involvement.”

Hiding behind the shield of imperial birthright?

Two of the three co-conspirators who were directly involved with Rasputin’s murder were of noble blood. One, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich was the first cousin to Nikolai II, the other, Count Felix Yusupov (the younger), was a wealthy aristocrat who married into the Romanov family. Once the crime was committed, they presupposed that the Grand Duke’s imperial birthright would shield them all from prosecution. Nevertheless, their presumption proved to be naïve.

Meantime, other ways to stall the investigation process were also played out. Given Yusupov’s wife’s (Princess Irina Alexandrovna and the emperor’s niece) imperial birthright, that circumstance precluded the police and court prosecutors from conducting a proper investigation of the first crime scene. The investigators could not enter the Yusupov Palace and thus they were unable to examine the large rear courtyard (where on the night, Dmitri Pavlovich’s vehicle was waiting to transport Rasputin’s corpse). Believing that no forensic evidence would be found in the small front courtyard that faced the Moika River, Felix Yusupov initially tolerated the investigators to fleetingly examine that location in the daylight, but shortly afterwards withdraw his permission. Fortunately, the second crime scene (where Rasputin’s body was eventually recovered), was a public place and given its remote location and the winter weather it, as the police photographs show, remained intact and uncontaminated.

It should be stressed that very few members of the extended family (other than Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Nikolai II’s sister) conceded that Grigorii Rasputin’s murder was a wrong act. To her credit, the empress demanded justice for Rasputin’s murder, which happened after Nikolai II firstly responded to the family petition with the words: “No one has the right to commit murder”.

“Stab, poison, shot, drown” – Cavalera Conspiracy, Rasputin

Did Rasputin’s murderers really try to poison him first?

No, that was a myth that can be found in Vladimir Purishkevich’s memoir and repeated by Felix Yusupov in his so-called recollection years later. Aside the fact that Rasputin detested sweet food, my book explains why such a setup was logically impossible.

“In Siberia you saw the Black Monk preach” – Therion, The Khlysti Evangelist

What was the Khlyst cult? And was Rasputin really a member?

The Khlyst sect was a 17thC movement that was prohibited movement in Russia and thus the Russian State was intent on finding adherents. Likewise, the Orthodox Church found it to be repugnant because the Khlyst conducted group sexual activity and self-flagellation. These acts, performed in a somnambulistic state of ecstasy was inspired through song, which supporters believed would offer them spiritual deliverance from their sins. All factors that confronted the teachings of the Church.

Rasputin was never a member of the Khlyst sect, a fact that was established by the Tobolsk Consistory Investigation that began in May 1907. At the end of their first Inquiry, in June 1908, the Tobolsk Eparchy handed down their verdict that Rasputin was a “Christian from … [the village of] Pokrovskoye.” The second inquiry (sought in secret by the empress) confirmed that Rasputin was a true Orthodox believer. After the third Inquiry concluded in November 1912 that he was indeed an Orthodox Christian, the church’s interest in Grigorii Rasputin had concluded. However, the matter did not end there. On 31 October 1917, a judicial investigator from the Provisional Government’s Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry unsealed the church file and was unable to find evidence that Grigorii Rasputin was associated with the Khlyst.

“Why do they dislike me?” – Jack Lucien, Rasputin

Why did so many Russians turn against Rasputin?

Essentially, it was the incessant gossip that eventually found its way into the media and then the podium of the Duma as early as 1912. Once the President of the Third Duma, Alexander Guchkov introduced the “Rasputin matter” the strannik (a religious wanderer) became not only a political creature, but fair game to all. Guchkov’s statements led people to believe that the material must be credible. Elsewhere, many who were caught up in the anti-Rasputin gossip in the salons and the Yacht Club where foreign ambassadors were members, reacted by vilifying a person who did not fit in with Russian fine society and worst of all, ostensibly tarnished the imperial throne. An attack on Rasputin was an indirect way of attacking the Empress, unpopular due to her German ancestry and her reluctance to be involved in society balls.

Gossip that affected Russia in the theaters of WWI

My book traces some of the originators of much of the gossip, which became so fanciful and malicious that it affected Russia politically and militarily in the theaters of the War. Initially the accusation included the presumption that Rasputin had wormed his way into the imperial palace. Society (including members of the Romanov family) believed that the ostracized empress had been debauched by Rasputin, that the peasant nominated government ministers, offered military advice to Nikolai II and that he sought a separate peace treaty with Germany whilst dabbling in espionage against Russia.

The gossiping was an affront to the imperial and Romanov families alike. Given the imperial family’s burden to maintain silence (taking such matters before the court was not feasible because the onus to prove Rasputin’s innocence would have in theory drawn in the emperor), how could one semi-literate peasant fend off all the gossip? As it turned out, several members of the Romanov family brought their insult into the public sphere and in 1916 reached the point that two of their own acted decisively to rid Russia of Grigorii Rasputin.

My research shows that although Britain had an interest in getting rid of Rasputin, British agents did not play a direct hand against Grigorii Rasputin. – Margarita Nelipa

What role did the British play in the plot against Rasputin, if any?

Russia enjoyed an alliance with Britain (and France). Once the War broke out, it was in Britain’s interest to ensure that Russia maintained its agreement and continued to fight the Germans until victory ensued. After attending the Duma and listening to the crucial 1 November 1916 speech as well as the gossip (some of which was alluded to above), British Ambassador George Buchanan and his friendship with Grand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich proved to be a toxic blend. Buchanan declared in one telegram that is now held in the British archives that he was informed that Rasputin would be murdered one week beforehand. Why would he be informed? At the crucial time, one British agent stationed in Petrograd and interestingly, a former Oxford university colleague of Felix Yusupov, was present at the palace. His role was to confirm that the British interest in Rasputin was realized to its satisfaction. Accordingly, my research shows that although Britain had an interest in getting rid of Rasputin, British agents did not play a direct hand against Grigorii Rasputin.

Additional trials/hearings pertaining to Rasputin’s murder took place in Great Britain and New York Supreme Court. Why did foreign jurisdictions look into Rasputin’s murder?

Yes, that was so. In 1932, Felix and his wife Irina sued film company MGM in Britain for libel in connection with the film titled “Rasputin and the Empress”. The questioning in the court had naturally raised questions about Rasputin’s murder, which were peripheral to the case and held no bearing on the verdict. Similar lines of questioning happened in the New York Supreme Court in 1965 after CBS televised a play based on Rasputin’s murder. In both jurisdictions, Yusupov knew that what he and his wife testified under oath about a Russian murder would not attract a guilty verdict.

I wanna be just like Rasputin – Jack Lucien, Rasputin

Have there been any attempts in the Russian Orthodox Church to canonize Rasputin?

Yes, there is a campaign by some religious folk and clergy in Russia who are seeking Rasputin’s canonization. The Synod of the Orthodox Church has stated unequivocally that it will not entertain this idea. Since there are conflicting accounts about Rasputin’s life, the question to prove or disprove them presents difficulties. Nonetheless, the enthusiasts continue to venerate Rasputin, creating icons that give him a saintly aura and treat him as a martyr akin to the martyred imperial family.

The police photographs show the killer(s) wanted to inflict the maximum punishment. – Margarita Nelipa

You have medico-legal training and experience. How do you interpret the physical evidence?

My interpretation of the forensic evidence may be read in Appendix Five of the book. The ballistic information outlined by Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich provided the crucial evidence that I needed. I can state without reservation that a Russian not a British military weapon was used to shoot at Rasputin’s forehead. Indeed, the questions lies, how can a Webley firearm (British military issue) having a calibre of 11.56mm firing unjacketed bullets create a discrete 6mm diameter wound?

Furthermore, after examining the police photographs of Rasputin’s corpse, I did not see any impact injury that mirrored the plaited pattern of the truncheon allegedly given to Yusupov by the Minister of Justice, to mete his form of justice. Professor Kosorotov stated all external impact injuries were those sustained by the body after it hit the bridge. The bone in the right cheek was shattered when the body was thrown from the bridge. Accordingly, I rejected Purishkevich’s and Yusupov’s recollections that one of them had used a truncheon at the first crime scene.

Finally, I would like to add that the police photographs show the killer(s) wanted to inflict the maximum punishment.

“He ruled the Russian land” – Boney M, Rasputin

Following the Russian Revolution, the provisional official Alexander Kerensky said, “Without Rasputin, there would have been no Lenin.” Do you agree?

I disagree with Alexander Kerensky’s claim. In my earlier work that relates to Alexander III’s reign, I mention Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin) and tell that he turned political after his brother was implicated and hanged for his participation in Alexander II’s assassination. That event caused Ulyanov to seek revenge against the reigning monarch, decades before Grigorii Rasputin became a household name in Russia. The imperial regime collapsed because Nikolai II was no longer supported by most of his family, the nobility, the Duma and the church. In the end, it was the betrayal by the elite military generals in the field that forced him to abdicate. Politically, Nikolai II was condemned because he would not give the Russian people a constitutional monarchy. If such a concession was made, then conceivably the brutal nature of the February Revolution may not have happened. The murder of Rasputin was one manifestation of these forces used against the sovereign, but if Rasputin never existed, the autocratic regime was still doomed.

In exile, Kerensky gave Rasputin too much credit by emphasizing the Siberian peasant had amassed political power – a conclusion that was refuted by Vladimir Rudnev who sat on Kerensky’s Extraordinary Committee of Inquiry as one of its prosecutors.

Vladimir Lenin came to power in November 1917 due to the ineptitude of the Provisional Government and its support for the socialist-minded Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers’ Deputies, both of which opposed the return of the monarchy (under Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich) and its institutions.

Thank you, Margarita Nelipa!

Literature on point:

Margarita Nelipa, Killing Rasputin: The Murder That Ended the Russian Empire (Denver, Wild Blue Press, 2017)

“Romanov Archives – Okhrana Surveillance Report on Rasputin: From the Red Archives,” Alexander Palace Time Machine (website)

Carolyn Harris, “The Murder of Rasputin, 100 Years Later,” Smithsonian (December 27, 2016)

I have read Killing Rasputin and it is fascinating. I thought that there was nothing I did not know about Rasputin, but, having read this book I know that I did not know all of it.

I agree, Marilyn. Killing Rasputin is chock-full of information and I’m impressed with the level of research it contains. And only a Russian author could have given us so many primary sources. Thanks for commenting!

I have to admit that I haven’t read the book yet but I fully intend to after reading this fascinating interview. I have long been interested in the Romanov family, ever since the movie “Nicholas and Alexandra” came out in December 1971. I’ve also read the classic account of Nicholas and Alexandra by Robert K Massie. I’m so glad that this author had access to so much new material to dispel a lot of the false beliefs of what happened and how much influence Rasputin had on the Imperial Family. I’m sure that reading this book will dispel a lot of the myths that are in my mind regarding Rasputin such as the telegram that supposedly “saved” Alexei. The results of the autopsy were entirely different than what I had been led to believe by the Massie biography and the movie. This is a really interesting topic and a very interesting interview, thank you.

I’m glad you liked it, Susan! That’s one of the great things about this book — the author is fluent in Russian, has experience in medico-legal issues, and was able to unearth new evidence. I think you’d really like the book. Thanks for commenting!

I would like to contact Margarita Nelipa, as I have written an article about Rasputin and years ago knew someone who claims to have known him. I do not use Facebook, only email. Helen Azar gave me her email address, but I have yet to make contact with her.

So, if you can find a way for me to contact her, I would appreciate it.

Dr. Simmons — I will write you an Email.

Hi

I would like to contact Margarita to organise an online lecture about Rasputin.

I would appreciate if you could put me in touch with her

I’ll ask her for her permission to share her email address with you and let you know. Thanks for your interest.