He put up a fine luncheon for us and added to it a quantity of great light-green plums, the pleasantest fruit in Germany…. Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad Greengages Anna Pavord, writing for the British newspaper Independent, calls them “most...

God! how delicious the memory of it!—I caught him escaping from his grave, and thrust him back into it. – Mark Twain, “A Dying Man’s Confession,” in Life on the Mississippi Murder and revenge. These two themes form the warp and weft in “A...

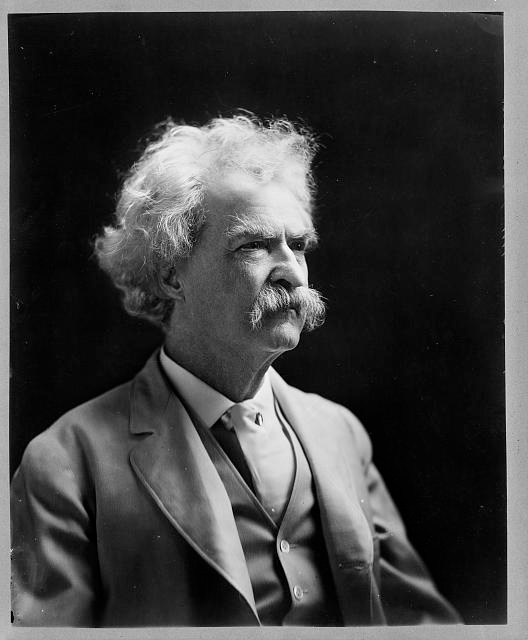

Germany’s lower Neckar Valley is Mark Twain country. This stretch of river, the locals will fondly tell you, inspired Huckleberry Finn. The author came to Germany in 1878 with writer’s block and Huck Finn half finished. Twain’s raft trip down the...

Did the church usher mistake him for a duke? And did Mark Twain mistake the empress for someone else? Mark Twain’s account of an encounter with Empress Augusta of Germany counts among his most hilarious sketches of Baden-Baden. It appears in A Tramp...

Real quick now – which saint killed the dragon? What’s the first name that comes to your mind? St. George. Is that what you thought? It’s what I thought, too. St. Mark’s Square in Venice sports two monolithic columns with figures on top. One is a...

Back to the Middle Ages? “Downstairs,” the receptionist said. “In the dungeon.” Armed with shampoo and a towel, I followed his directions across the courtyard and down two flights of stairs. We had booked rooms in a medieval German castle, and this...

Blanca Knodel is standing on her “balcony” and the wind whips her hair. The wind isn’t surprising. Her balcony is a walkway around a set of turrets 105 feet above the ground. Blanca Knodel is a tower keeper in the German city of Bad Wimpfen, and...

They are Germany’s most famous stuffed animals, at least for Americans. A snowy owl and a wildcat lurk in the taxidermy display cases of the Langbein Museum in Hirschhorn, Germany. They’re renowned because Mark Twain wrote about them in A Tramp...

It can happen to anybody. Mark Twain had started several new books when it struck in 1878. His solution to writer’s block might surprise you. And the results probably surprised him. Mark Twain in Heidelberg Twain decided a change of scenery would...

Recent Comments