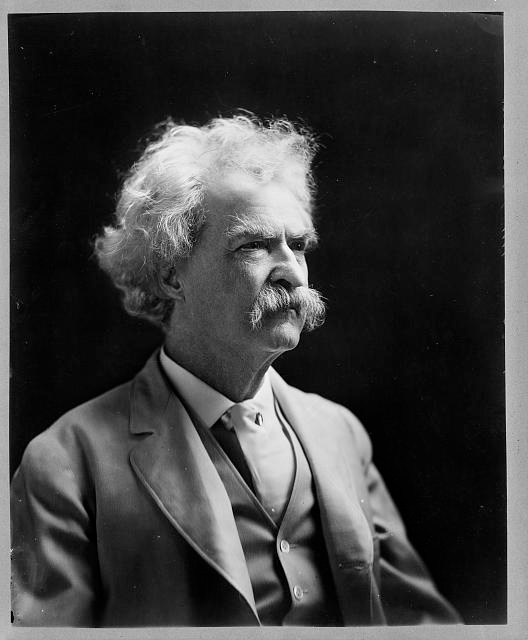

Germany’s lower Neckar Valley is Mark Twain country. This stretch of river, the locals will fondly tell you, inspired Huckleberry Finn. The author came to Germany in 1878 with writer’s block and Huck Finn half finished. Twain’s raft trip down the...

It can happen to anybody. Mark Twain had started several new books when it struck in 1878. His solution to writer’s block might surprise you. And the results probably surprised him. Mark Twain in Heidelberg Twain decided a change of scenery would...

Recent Comments