Fanny Workman refused to conform. That refusal developed into what Germans call a “red thread” – the common theme that explained much of her life (1859-1925), and in particular, her record-breaking adventures. As the daughter of a Massachusetts...

It has got to be one of Germany’s best kept secrets. Not just the six-pointed star hanging in front of the house, but the homebrewed beer the star represents. The Zoigl tradition has almost gone extinct in Germany, and if you want to experience it...

June 1912 marks the 107th anniversary of a murder so gruesome it gave rise to urban legend. You’ve probably heard the story. Someone hid in an attic and snuck down to butcher an entire family during the night. It really happened. With an entire...

Agatha Christie — she wrote murder mysteries; we all know that. But this is probably what you didn’t know: Agatha Christie was also a pharmacist and the medical descriptions in her books were so accurate they actually saved lives. They even...

An Interview with Ripperologist Richard Jones Jack the Ripper: What makes the case so fascinating? Some people say it’s the Sherlock Holmes aspect: a riddle and investigation methods everyone can follow. Other people say it offers a window...

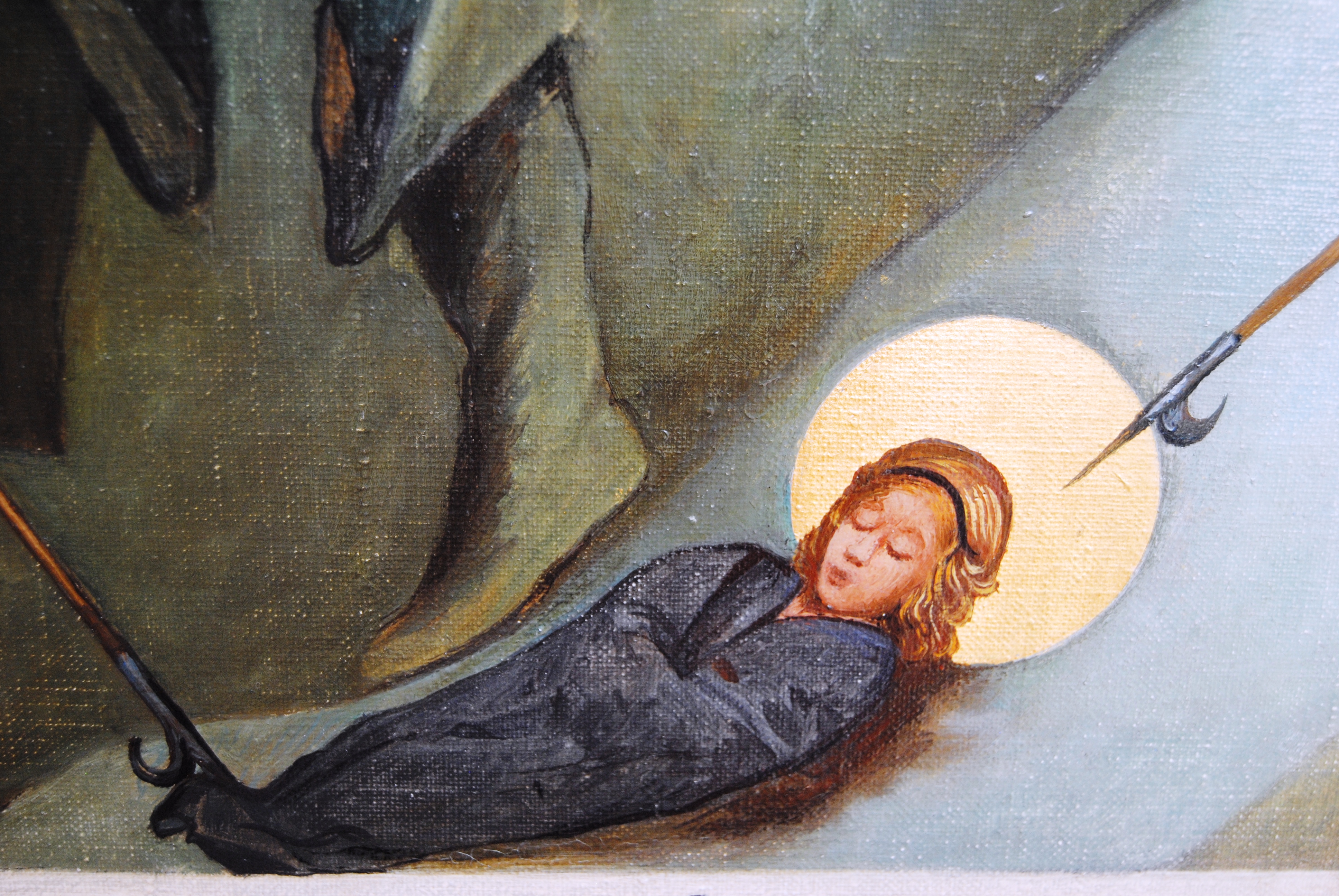

Regiswindis: Murder of an Innocent — Deutsche Übersetzung folgt She was only seven years old, so the story goes. Regiswindis, the daughter of Count Ernst in the German town Lauffen am Neckar, grew up in her father’s castle. That’s where...

Winston Churchill encounters Lincoln: The most famous White House ghost story What would you do if you stepped out of the bath tub stark naked – with only a cigar dangling from your mouth – to encounter the ghost of Abraham Lincoln standing in your...

Stolen clothing. Does the greatest fear of every skinny dipper ever haunt you? Is a bather’s stolen clothing is just a TV trope? Or do you worry about someone stealing your clothes when you take a dip in the pool or lake? Maybe you should. A German...

An Interview with Russian Historian Margarita Nelipa Grigorii Rasputin: Russian mystic, counselor to the imperial family, and murder victim. Apart from the execution of the Romanov family in July 1918, the murder of Rasputin in December 1916 is...

Just how many victims did Jack the Ripper have? The number of canonical victims is five, but some people say there are more, and some less. What measuring sticks do Ripperologists use to figure their lists? Historian and true crime aficionado Cal...

Recent Comments