Criminal investigations in the 17th and 18th centuries differed from the ones we know today. Forget the police. They didn’t exist yet. Superstition played a big role. City and castle walls helped entrap crooks; citizens pitched in with the chase.

Jan Wiechert and the Bad Ole Times

In fact, historical true crime cases make an exciting way to learn local history. That’s what archivist Jan Wiechert thinks. And he doesn’t think the “good ole times” were necessarily good. He selected a handful of intriguing crimes from the dusty pages of Hohenlohe Central Archiv in Neuenstein and created an anthology appropriately dubbed “Bad Ole Times” (Böse Alte Zeit, Gmeiner Verlag, 2017).

Jan Wiechert’s stories offer so much drama I didn’t realize, until I finished the book, how much history I’d painlessly picked up. Is there a more fun way to learn history than a true crime format? Wiechert doesn’t think so and joins us for an interview today to show why.

An interview in German follows the English version. Ein Interview auf Deutsch folgt der englischen Version.

Interview with German true crime author Jan Wiechert

There weren’t any police in the 17th century. How were criminals investigated and caught?

Often the normal citizens had to look for the criminal when someone committed a crime. In cities, a magistrate or bailiff drummed the people together; in villages is was the mayor who organized a patrol. Of course, the crook often slipped through their fingers, but when he was caught, it was the citizen’s duty to detain him securely and to deliver him up the authorities.

What role did superstition play in the administration of justice?

The belief in the effects of inscrutable, magic powers played a significant role in every part of the people’s everyday life. During the period of the witch trials, it had dramatic consequences for criminal justice issues. In history films, the witch hunter is usually an evil, ruthless, and fanatical brute. Without brushing aside the victim’s suffering, you also have to try to be fair to the persecutors. They believed in the tangible intervention of the incarnate devil in the world of man – that was as self-evident for them as it is for us to believe the light will go on when we flip the switch.

What were the best investigative techniques of the 17th and 18th centuries?

For lack of scientific knowledge, criminal investigations essentially evolved from interrogations, through which torture was employed under certain circumstances. I find it interesting that in cases of doubt, the technique of confrontations was often used. Instead of saying to the suspect: “The witness XYZ said something different!” one simply brought the suspect and witness together and interrogated them together.

Can you compare the 17th and 18th century warrants of apprehension with the wanted posters of the Wild West?

In the 16th and 17th century, wanted posters were usually handwritten and directed to the authorities of surrounding regions. Sometimes a messenger was sent with the poster, who collected signatures on paper or even seals to show he was really at a certain location, so we can reconstruct his route today. That changed in the 18th century, especially with the advent of bands of robbers and thieves. From this time period there exist printed wanted posters with all the information about the person sought that could be hung up or – sometimes even from the church pulpit – read out loud.

How did city and castle walls help to catch criminals?

It could indeed be helpful to have a city wall when you knew a criminal was located in the city. You could simply close the gates and step up the controls before you started the search. But for the authorities, the protective factor was more important. To a certain extent, medieval walls were useless as a military defense against firearms, but they could keep thieves and tricksters from sneaking in.

If you were Jean Travenier – the young thief in your book – how would you have escaped justice after you had climbed over the castle walls?

Travenier – nice that you’re referring to my favorite criminal – actually did everything right in that he traveled as quickly as possible to another territory. The multitude of small German states worked as a real advantage for fugitives. That he was nevertheless caught was just bad luck: bad luck that he was seen on the run, bad luck, that the city of Schwäbisch Hall cooperated so quickly and well with the earls of Hohenlohe, and bad luck, that he fell asleep above the table at the inn. But no wonder: He had already fun 30 kilometers that day. I can’t begrudge him his escape.

You sold out of the first edition of your book after only four months….

Yes, I was pleasantly surprised. Obviously my plan was to tell social and daily stories to a regional market, through the principle that “crime sells,” and in a colloquial, non-academic language without the readers shuddering with the memories of their history classes.

Are you planning another book?

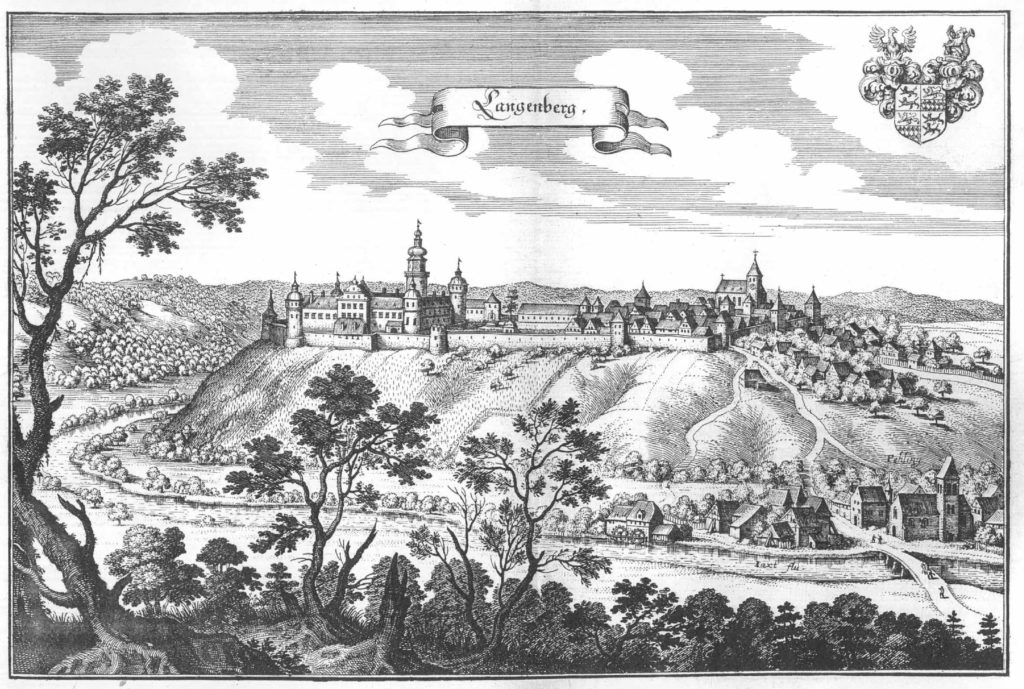

Just one? A half bookcase is swirling around inside my head and in the Hohenlohe Central Archives, many exciting stories are slumbering that desperately need to be told. The next book will appear in mid 2018 and it will delve deeply into a murder case that occurred in 1777 in Langenburg.

Thank you, Jan Wiechert!

If you enjoyed this post, then you might also like Medieval City Structure and True Crime History. That post’s about how city walls affected criminals ability to escape.

Interview mit Jan Wiechert auf Deutsch

Es gab im 17. Jahrhundert keine Polizei. Wie wurde Straftäter ermittelt und erwischt?

Wenn ein Verbrechen bekannt wurde, mussten oft die normalen Bürger nach dem Täter suchen. In Städten trommelte der Vogt oder Amtmann seine Leute zusammen, in Dörfern war es der Schultheiß, der eine Streife organisierte. Oft ging der Täter natürlich auch durch die Lappen, aber wenn er gefasst wurde, war es die Pflicht der Bürger, ihn sicher zu verwahren und an die Obrigkeit auszuliefern.

Welche Rolle spielte der Aberglauben in der Justiz?

Der Glaube an das Wirken undurchschaubarer, magischer Kräfte spielte im gesamten Alltag der Menschen eine bedeutende Rolle. In Fragen der Strafjustiz hatte das, besonders in Zeiten der Hexenverfolgung, dramatische Auswirkungen. Im Historienfilm ist der Hexenjäger meist ein böser, skrupelloser und fanatischer Unmensch. Ohne das Leid der Opfer herunterzuspielen, muss man auch versuchen den Verfolgern gerecht zu werden. Sie glaubten an das konkrete Eingreifen des leibhaftigen Teufels in die Welt der Menschen – so selbstverständlich, wie wir daran glauben, dass das Licht angeht, wenn wir den Schalter drücken.

Was waren die besten Ermittlungstechniken der 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts?

Mangels naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse bestanden Ermittlungen im Wesentlichen aus Befragungen, bei denen unter bestimmten Umständen die Folter eingesetzt wurde. Interessant finde ich, dass man in Zweifelsfällen oft auf das Mittel der Konfrontation setzte. Statt dem Angeklagten zu sagen: „Der Zeuge XY hat aber etwas ganz anderes gesagt!“ führte man ihn einfach mit dem Zeugen zusammen und befragte sie gemeinsam.

Kann man die Steckbriefe der 17. und 18. Jh. mit den “Wanted”-Postern des wilden Westen vergleichen?

Im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert waren Steckbriefe meist handschriftlich und an die Obrigkeit umliegender Gebiete gerichtet. Manchmal wurde ein Bote mit dem Brief losgeschickt, der sich auf dem Papier unterschreiben oder sogar siegeln ließ, dass er wirklich an einem bestimmten Ort war, so dass man heute noch seine Route rekonstruieren kann. Im 18. Jahrhundert, vor allem mit dem Aufkommen von Räuber- und Diebesbanden änderte sich das. Aus dieser Zeit liegen wirklich gedruckte Steckbriefe mit allen Angaben zu den gesuchten Personen vor, die ausgehängt oder – manchmal sogar von der Kirchenkanzel aus – vergelesen werden konnten.

Wie halfen Stadt- und Burgmauern dabei, Straftäter zu fangen?

Es konnte schon hilfreich sein, eine Stadtmauer zu haben, wenn man erfuhr, dass sich ein Straftäter in der Stadt befand. Man konnte schlicht die Tore verschließen und die Kontrolle verstärken lassen, bevor man sich auf die Suche machte. Für die Obrigkeit war die schützende Funktion aber wichtiger. Mittelalterliche Mauern waren zur militärischen Verteidigung gegen Feuerwaffen zwar einigermaßen nutzlos, aber sie konnten das Einschleichen von Dieben und Gaunern verhindern.

Wenn Sie Jean Travenier — der junge Dieb in Ihrem Buch — gewesen wären, wie wären Sie der Justiz entkommen, nachdem Sie über die Burgmauer kletterten?

Tavernier – schön, dass Sie auf einen meiner Lieblingsverbrecher anspielen – hat eigentlich alles richtig gemacht, indem er sich so schnell wie möglich in ein anderes Territorium begeben hat. Die deutsche Kleinstaaterei war für Flüchtige eben ein echter Vorteil. Dass er doch gefasst wurde war reines Pech: Pech, dass er auf der Flucht gesehen wurde, Pech, dass die Stadt Schwäbisch Hall so schnell und gut mit den Grafen von Hohenlohe kooperierte und Pech, dass er über dem Wirtshaustisch eingeschlafen ist. Aber kein Wunder: er war an diesem Tag auch schon 30 Kilometer gelaufen. Ich hätte ihm die Flucht jedenfalls gegönnt.

Sie haben nach vier Monaten schon die erste Auflage ausverkauft….

Ja, das hat mich positiv überrascht. Offenbar ging mein Plan auf, durch regionalen Bezug, das Prinzip „Crime sells“ und eine etwas lockere, unakademische Sprache Sozial- und Alltagsgeschichte vermitteln zu können, ohne dass die Leute mit Grausen an ihren Geschichtsunterricht zurückdenken.

Planen Sie noch ein Buch?

Nur eines!? In meinem Kopf schwirrt ein halbes Bücherregal herum und im Hohenlohe-Zentralarchiv schlummern noch viele spannende Geschichten, die dringend mal wieder erzählt werden müssen. Das nächste Buch wird Mitte 2018 erscheinen und sich intensiv mit einem Mordfall beschäftigen, der sich 1777 in Langenburg zugetragen hat.

Love mysteries!!!

Me too! Especially historical ones.

Hello Ann Marie Ackermann

Thank you for your latest Newsletter. I hope this means you are fully recovered from your illness.

I am looking forward to your next one.

Best regards Jerry

Thanks, Jerry, and yes, I’m doing better. You should be seeing more blog posts coming out on my site.

This is an interesting interview and it increases my interest in criminal stories that took place in the past. I never thought how city walls could also be helpful in keeping people inside!