A triple insult As I scanned the ink scratched onto the yellowing letter, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for its author. It’s one thing to be falsely accused of a murder. It’s another to be driven out of your country. But the final insult is to...

A national mystery The Virginia Historical Society inherited a national mystery in 1981. That’s when it obtained the deButts-Ely family papers. The collection contains Robert E. Lee correspondence, and among it, a surprising letter...

There’s only one thing more disconcerting that waking up and hearing strange noises in the night. Waking up and finding a stranger in your bed is worse. Even if it’s only a small child. One of my favorite anecdotes of any Civil War general...

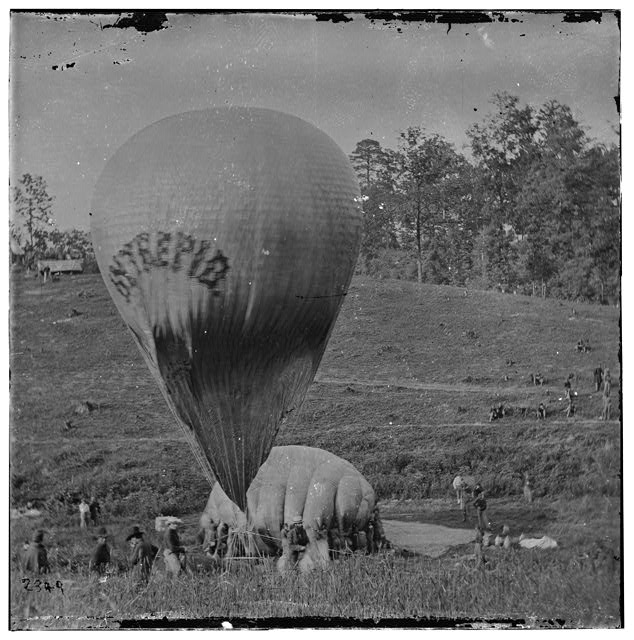

Spycraft rose to new levels during the Civil War. One of the most interesting innovations was ballooning. These five fun facts provide a brief introduction to what was then cutting edge military technology. Civil War balloons were not the...

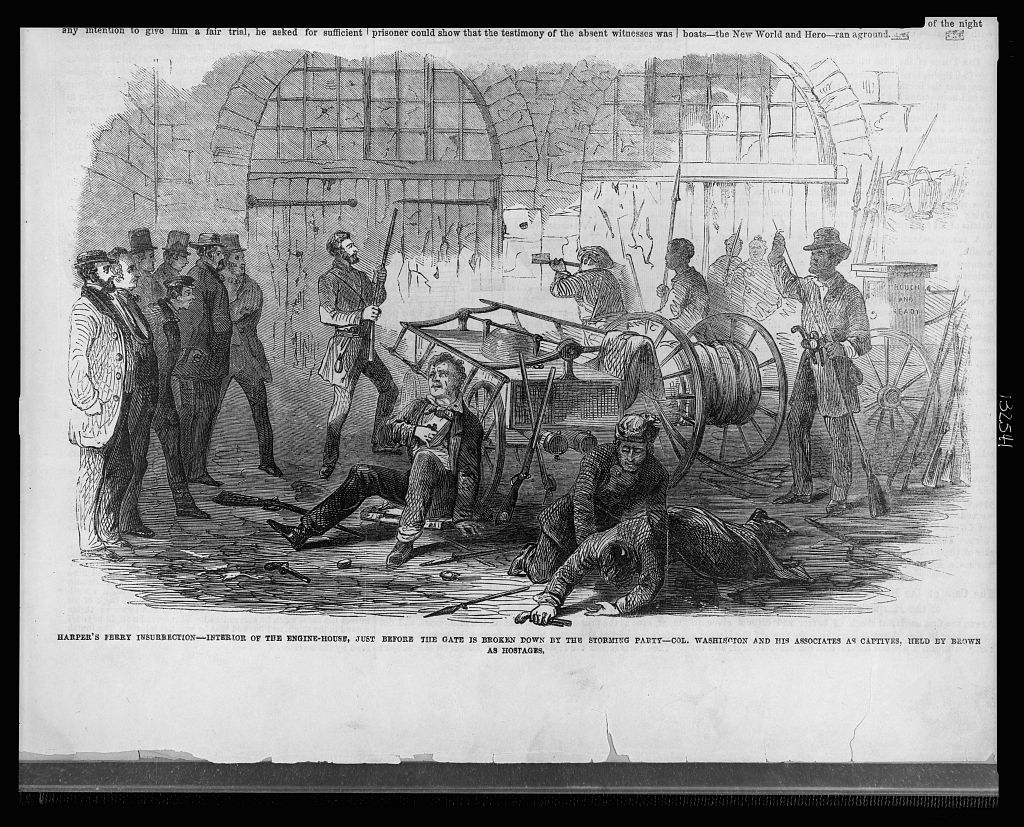

More than any other event, it was John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry that lit the fuse of North-South tension and ignited the Civil War. Brown planned the raid for two years in advance, so it was no mistake that the first thing he did when he...

The Mississippi as the key to commerce Even if the Civil War never happened, and even if Robert E. Lee never became president of Washington and Lee University, we would still probably know him today. He changed American history not only as a general...

Recent Comments